There was a time when the compact camera had quite a market. These cameras sat somewhere between the larger sensor cameras (full-frame/APS-C), and tiny sensor “pocket” cameras. The tiny sensor cameras died off with the evolution of the smartphone. Nowadays there aren’t many compacts left, perhaps victims to the success of the smartphone cameras, or to the success of mirrorless. Contenders now include the Ricoh GR series, the Fujifilm X100V, and Sony RX100. A mirrorless offers almost the same form factor with interchangeable lenses, and more features. Compacts often try to do too much, and maybe that is a function of modern technology where smaller does not mean reduced functional capacity. Many compacts do nothing at all particularly well, but maybe they were never meant to. They offer too many controls to be simple, but too few to show versatility. They are often built by trying to cram too much technology into the one thing that unifies them all – space. For a compact camera should be exactly that, compact. If they are compact, it is unlikely they will win awards for ergonomics. Compact cameras with small footprints, may not fit into everyone’s hands comfortably.

Compact cameras are exceptional for the purposes of street photography. The best example of this is legendary Japanese street photographer Daidō Moriyama. He has used Ricoh compacts for years, from the early GR film series to the digital GR.

“The GR has been my favorite since it was a film camera. Because I’m so used to it, I felt comfortable with the new GR III immediately. When I shoot with a 28mm fixed lens machine, I remember my old days. Comfortable enough to take photographs to your heart’s content. For my street photography, the camera must be compact and light-weighted.”

Daidō Moriyama

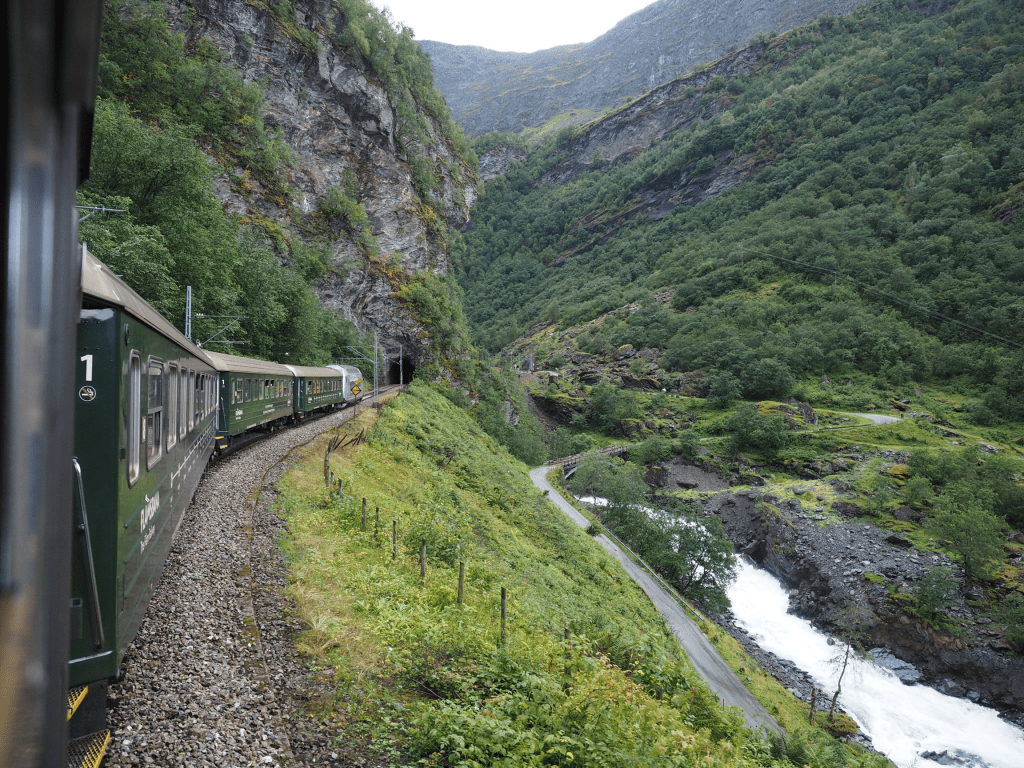

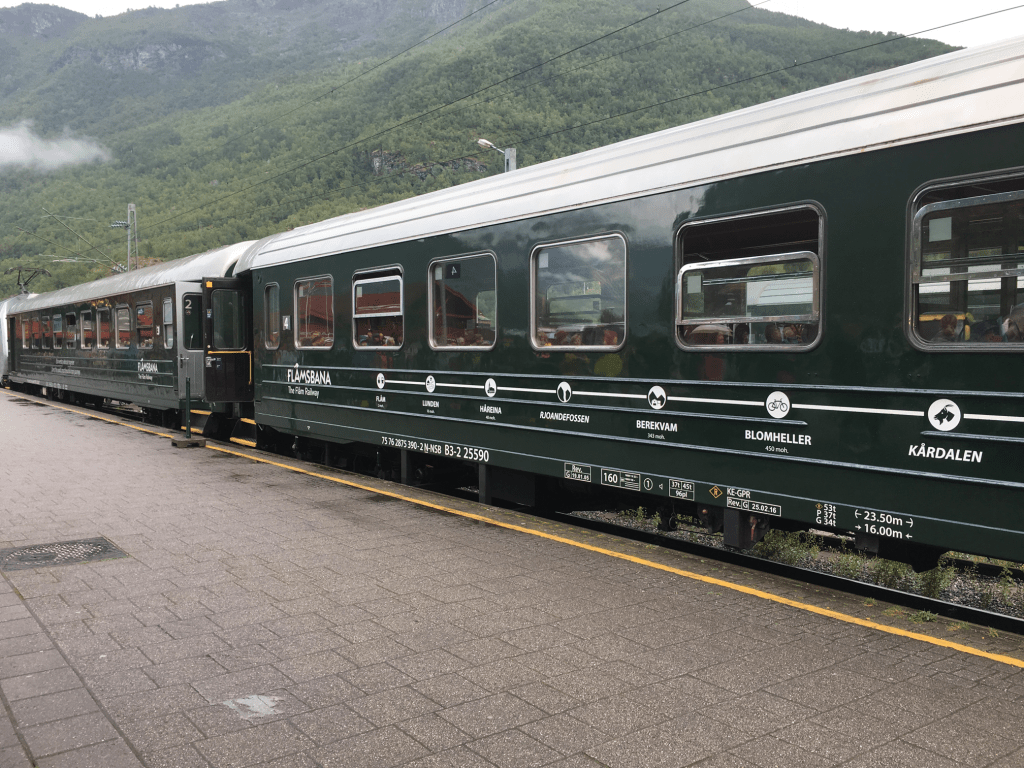

But here’s the thing, I don’t buy a compact to be the pinnacle of cameras. The job of the compact is to be compact. It should offer a good amount of features, but obviously cannot offer them all. The role of the compact in my life is simple – pocketable, easy to use, small, inconspicuous. It’s for that reason, my GR III sits around the kitchen for photographing recipes, or slips into a pocket for a walk about town. It’s small, compact, and oh so discreet. You can get into trouble in places like transit systems using mirrorless cameras because they seem too professional, but compacts? Compacts scream inconspicuous.

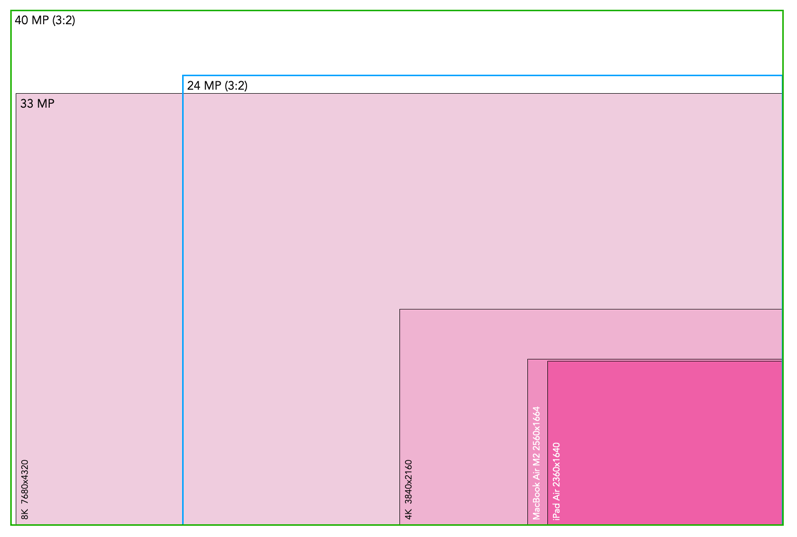

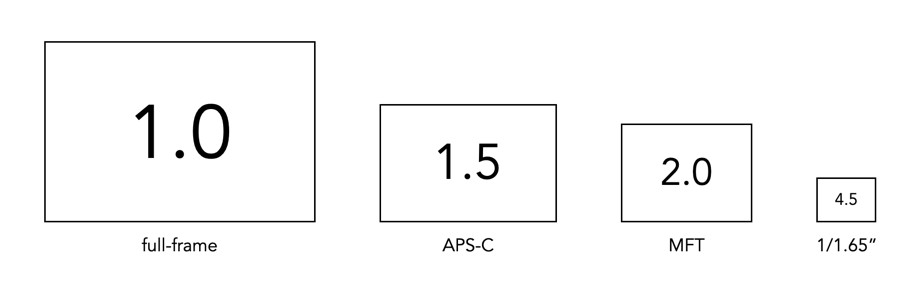

It is of course impossible to find the perfect camera – it doesn’t exist. Compact cameras are even less so, but the modern ones offers a good amount of technology and convenience. The Ricoh GR III for example offers image stabilization, and snappy focus, at the expense of loosing the flash (not something I use much anyways), not a great battery life (carry an extra), and no weather sealing (not that big a deal). It’s low-light performance is impressive, and I don’t need much more than a 28mm equivalent lens. It’s role is street-photography, or kitchen-photography, or back-up travel camera, for taking photographs in those places where photography is technically “not allowed”. It also offers a 24MP APS-C sensor, which is more pixels than anyone needs. In fact these cameras could likely get even better if we ditched some of the onboard shrot. Compacts don’t necessarily need 4K video, or 300-point AF tracking. The more features, and customization, the more the likelihood that you will loose track of what is going on.

| Pros | versatility – Fills a niche between smartphones and mirrorless cameras. macro – Many provide some sort of capacity to take close-up photos. small – Unobtrusive, and lightweight, making them easy to carry. automatic – No fiddling with settings and missing the shot. |

| Cons | limited control – Lacks low-level controls found in interchangeable lens cameras. low-light – Often not well suited to low-light conditions. fixed lens – Not as flexible as interchangeable lens cameras. battery – Shorter battery life because of the smaller battery. |

This is the fourth compact I’ve owned. The first was a Canon Powershot G9, then the Fuji X10, followed by the Leica D-Lux6 (likely the only Leica I will ever own). The Ricoh GR III provides me with the same sensor size as my Fuji X-H1, but is much easier to take some places when travelling, and provides much more in the way of versatility than does my iPhone 14, and twice the resolution.

Further reading:

- Ricoh GR III review: A powerful compact camera that’s far from flawless – Brett Day (2021)

- Ricoh GR III Street Photography Review: Long Live the King! – Karl Edwards (2019)

- Still the best: Ricoh GR III Long Term Review – Josh, Compact Shooter (2020)