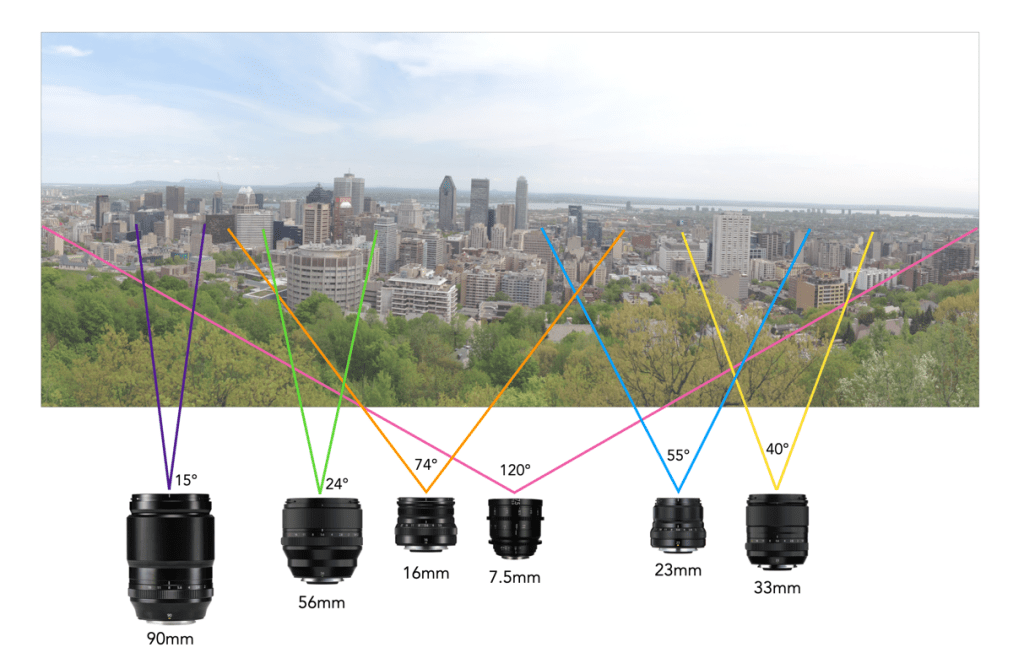

Once you have chosen a particular camera, (and manufacturer) it is time to think about lenses. Most people will buy a camera with some sort of kit lens attached, usually because it is cheaper. Others buy just the camera body, and outfit it accordingly, but it often a vast maw of choices. Lens choice is usually foremost about need, and ultimately focal length. What are you going to be shooting – portraits, landscapes, architecture? Then it becomes a balancing act of lens characteristics. If you choose, say a 35mm lens on an APS-C sensor, so 50mm equivalent, then it’s about things like size/weight (e.g. for travelling), weatherproofing, maximum aperture, build (metal/plastic), and of course cost.

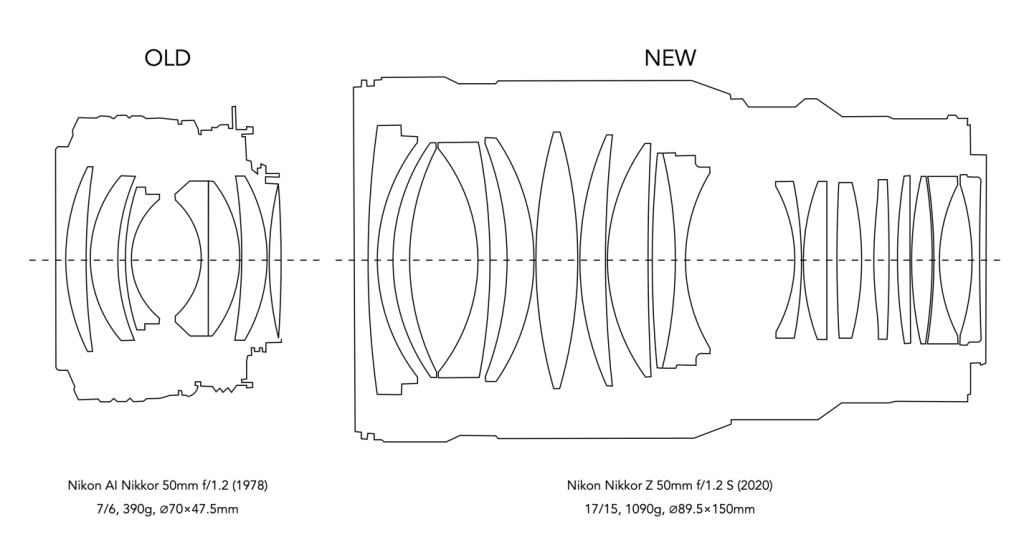

This leads us to the question some people end up pondering – do you buy a lens from the camera manufacturer or a third-party? Firstly, let’s consider each type of lens. Lenses produced by the camera manufacturer are often considered the creme-de-la-creme. They are designed from the bottom up, as integral components of the system. Quality and compatibility are the reasons why professional photographers stick with first-party lenses. These particular lenses are made specifically for the camera brands that they carry, so they are not compatible with any other manufacturers or brands.

Third-party lenses on the other hand, are often designed by lens companies from the perspective of creating a variety of lenses that will fit cameras from multiple manufacturers with the simple change of a mount (and tweaking some other specs). For example Sigma produces a 28mm f/1.4 lens that is available in Canon (EF), Nikon (F), Sony (E), and Leica (L) mounts. As with many manufactured items there are different levels of third-party lens manufacturers, from precision, high-priced lenses to mass-produced budget-oriented lenses. Third-party lenses can also be differentiated into long-established ”old-school”, and newer lens manufacturers. Voigtländer and Zeiss are good examples of well-established 3rd party lens makers who produce higher-end “boutique” glass.

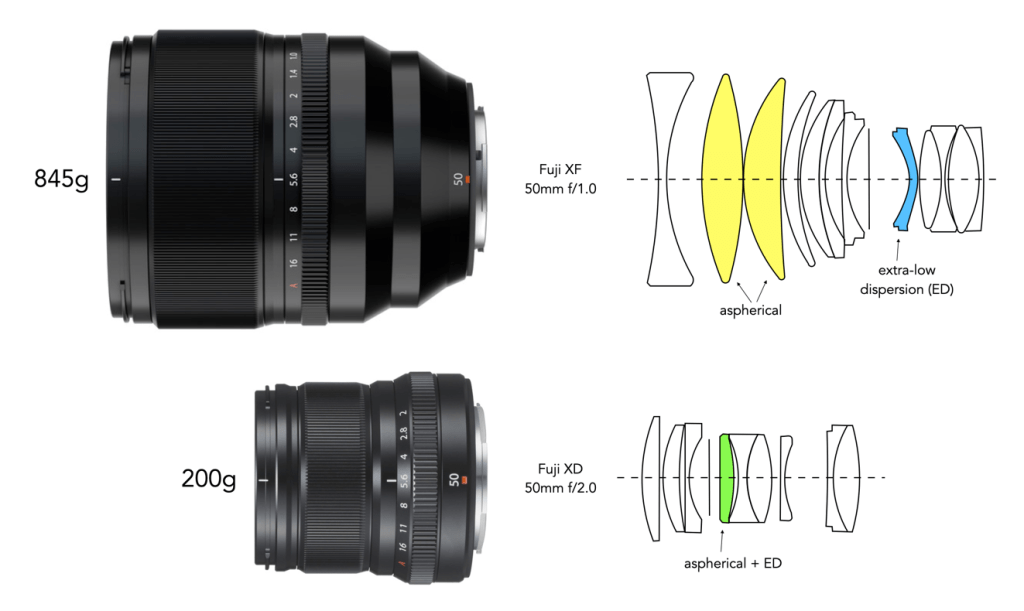

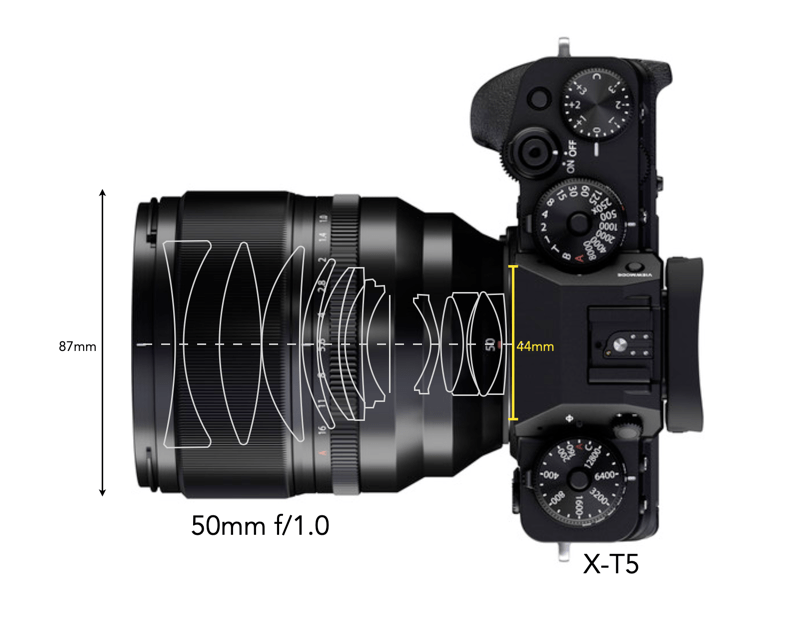

So why choose a 3rd party lens? There are many reasons. I suspect most people go that route because of the general affordability of the lenses. This also makes sense if someone wants to experiment with a particular lens, but doesn’t want to pay a small fortune. Affordability is often perceived as a sign that the lenses are inferior from the viewpoint of capabilities or build, but this isn’t always the case. Sometimes the lower price is a factor of trades-offs: manual focus instead of auto-focus capabilities, polycarbonate lens body instead of metal, etc. Some third-party lenses offer functionalities such as large apertures, e.g. f/1.0, or a smaller, lighter build, or even a lens not offered by a camera manufacturer, e.g. fish-eye lenses. For example the shortest focal length produced by Fuji is 8mm f/3.5 (12mm eq.), however it is US$800. An alternative for the photographer wishing to experiment with fish-eye lenses is the Tokina SZ 8mm f/2.8 (US$300).

What about disadvantages? Well the flip-side of 3rd party lenses is the lower-cost is that the lenses are sometimes optimized for lower cost. There may be some manufacturers that sacrifice the quality of materials used in lens manufacturing, and hence lens durability for a lower price. There is also the chance that the lens will not be 100% compatible with every one of the cameras it fits on. This goes back to the materials/build sacrifices made in construction. Another “disadvantage” for some is that many third-party lenses is manual focus. This is partially because it is cheaper and easier to produce a lens without focusing mechanisms, and electronic connections to the camera. However manual focusing is not a huge issue, because of functions built-into many cameras these days which assist with manual focusing, e.g. focus-peaking.

Actually the main problem in choosing lenses from 3rd-party manufacturers is differentiating between them. Because apart from the price differential, the specs of many lenses look quite similar. Below are five third-party 12mm lenses for the Fuji-X system (Fuji does not make a 12mm, the closest is a 14mm f2.8).

| Aperture range | Elements/group | Weight | Barrel material | Cost (US$) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zeiss Touit | f/2.8 − 22 | 11/8 | 260g | metal | $999 |

| Rokinson | f/2.0 − 22 | 12/10 | 260g | metal + plastic | $399 |

| Meike | f/2.8 − 22 | 12/10 | 326g | metal | $230 |

| Pergear | f/2.0 − 22 | 12/9 | 300g | metal | $165 |

| 7Artisans | f/2.8 − 16 | 8/10 | 265g | metal | $149 |

So when you get to choosing a lens, you may be swayed by the extremely reasonable prices of some of the 3rd party lenses. So what to do? Well the first thing to do is to find a website that maintains an updated list of lenses for a particular system. I’ll give examples of Fuji-X, because that has become my core system. Here is a good list from Alik Griffin. Third party lens manufacturers can be separated based partially on the quality of optics (and let’s face it, cost). At the end of the day, the actual lens you choose will depend on budget and individual requirements. If you decide to buy a third-party lens, make sure you do a good amount of research into the lens. Check out independent reviews from photographers, both professional and hobbiest, that have used the lens.