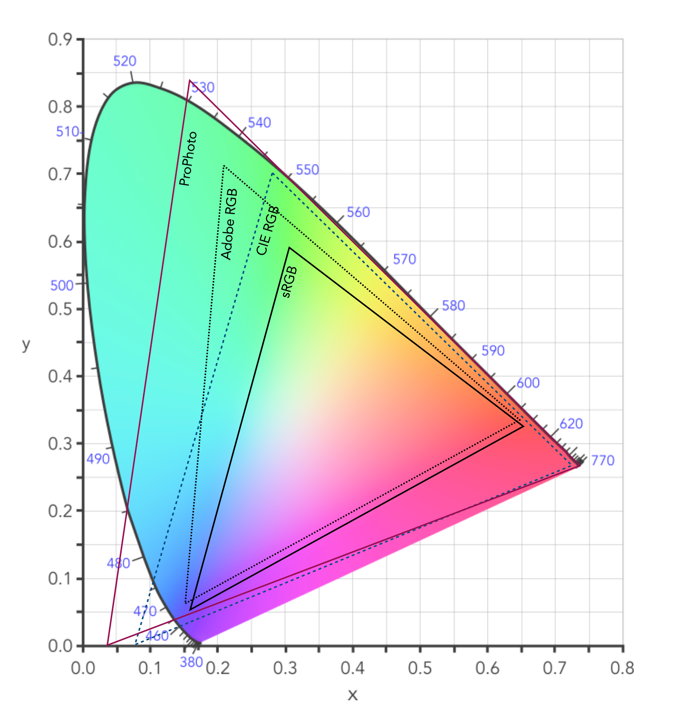

The Commission Internationale de l’Eclairage (French for International Commission on Illumination) , or CIE is an organization formed in 1913 to create international standards related to light and colour. In 1931, CIE introduced CIE1931, or CIEXYZ, a colorimetric colour space created in order to map out all the colours that can be perceived by the human eye. CIEXYZ was based on statistics derived from extensive measurements of human visual perception under controlled conditions.

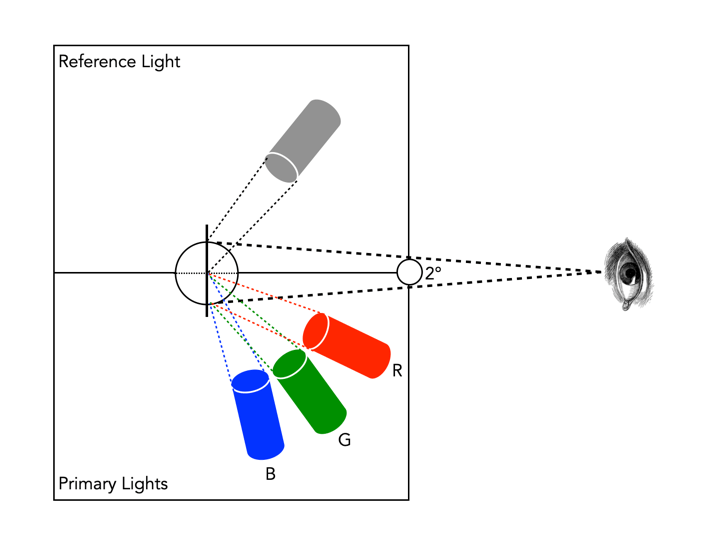

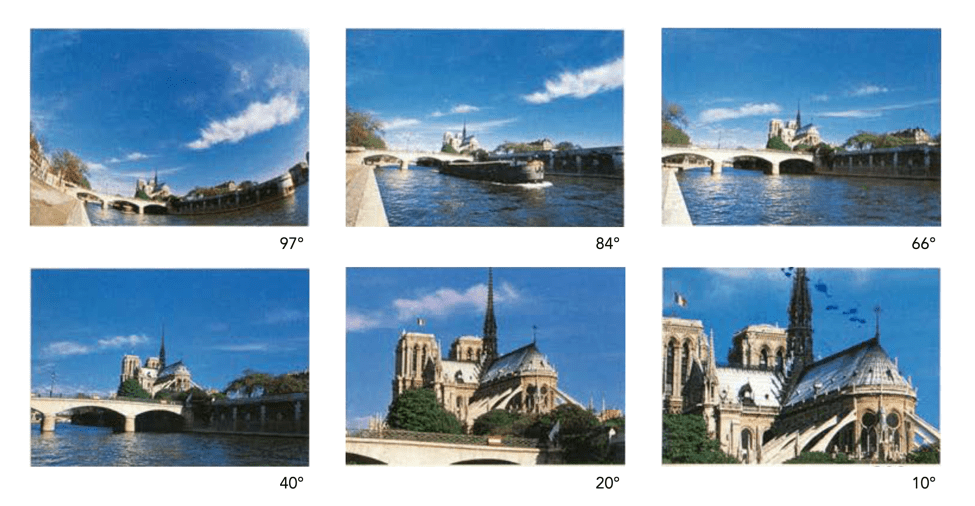

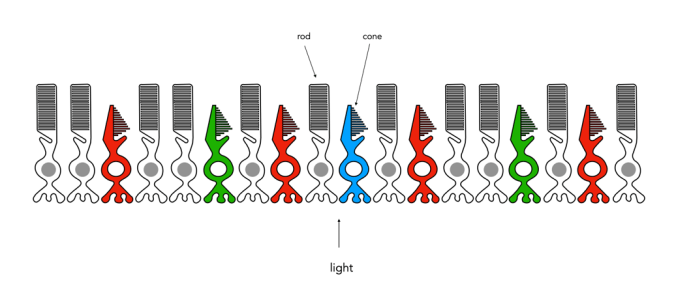

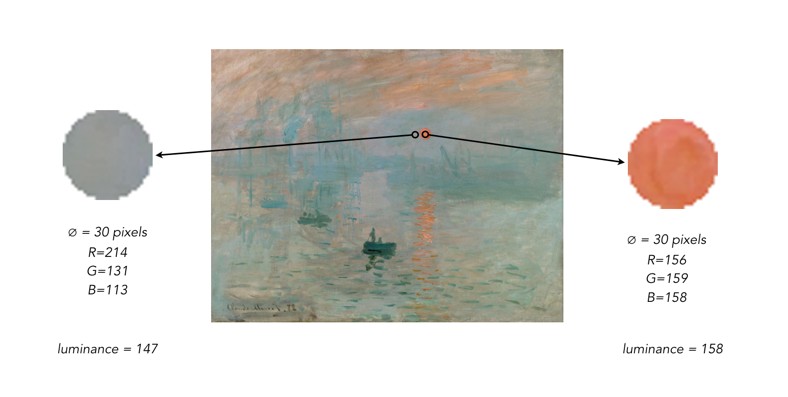

In the 1920s, colour matching experiments were performed independently by physicists W. David Wright and John Guild, both in England [2]. The experiments were carried out with 7 (Guild) and 10 (Wright) people. Each experiment involved a subject looking through a hole which allowed for a 2° field of view. On one side was a reference colour projected by a light source, while on the other were three adjustable light sources (the primaries were set to R=700.0nm, G=546.1nm, and B=435.8nm.). The observer would then adjust the values of three primary lights until they can produce a colour indistinguishable from a reference light. This was repeated for every visible wavelength. The result of the colour-matching experiments was a table of RGB triplets for each wavelength. These experiments were not about describing colours with qualities like hue and saturation, but rather just attempt to explain how combinations of light appear to be the same colour to most people.

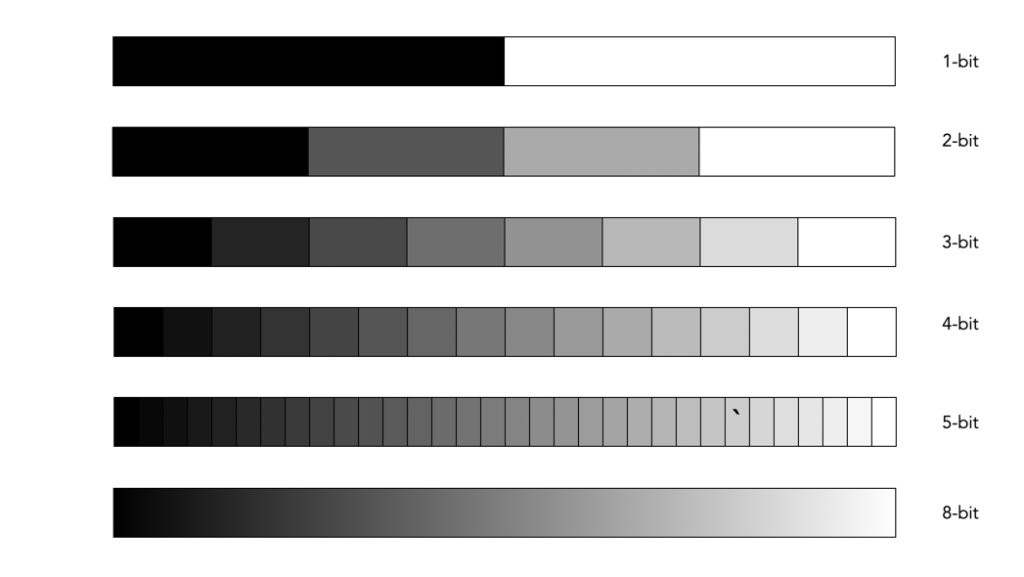

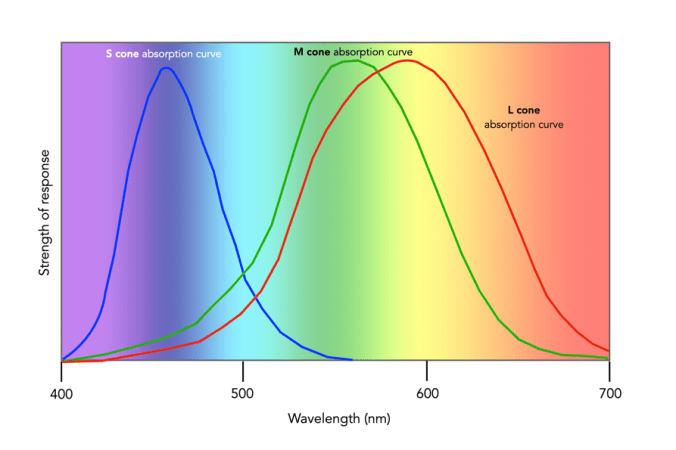

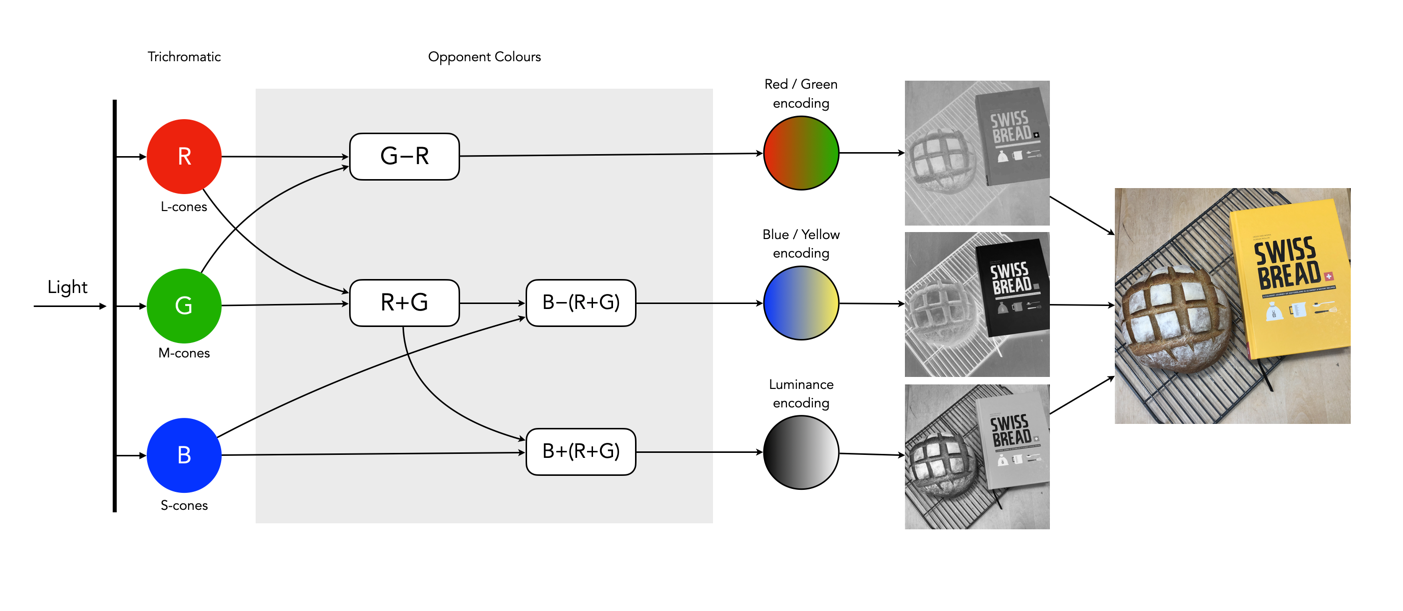

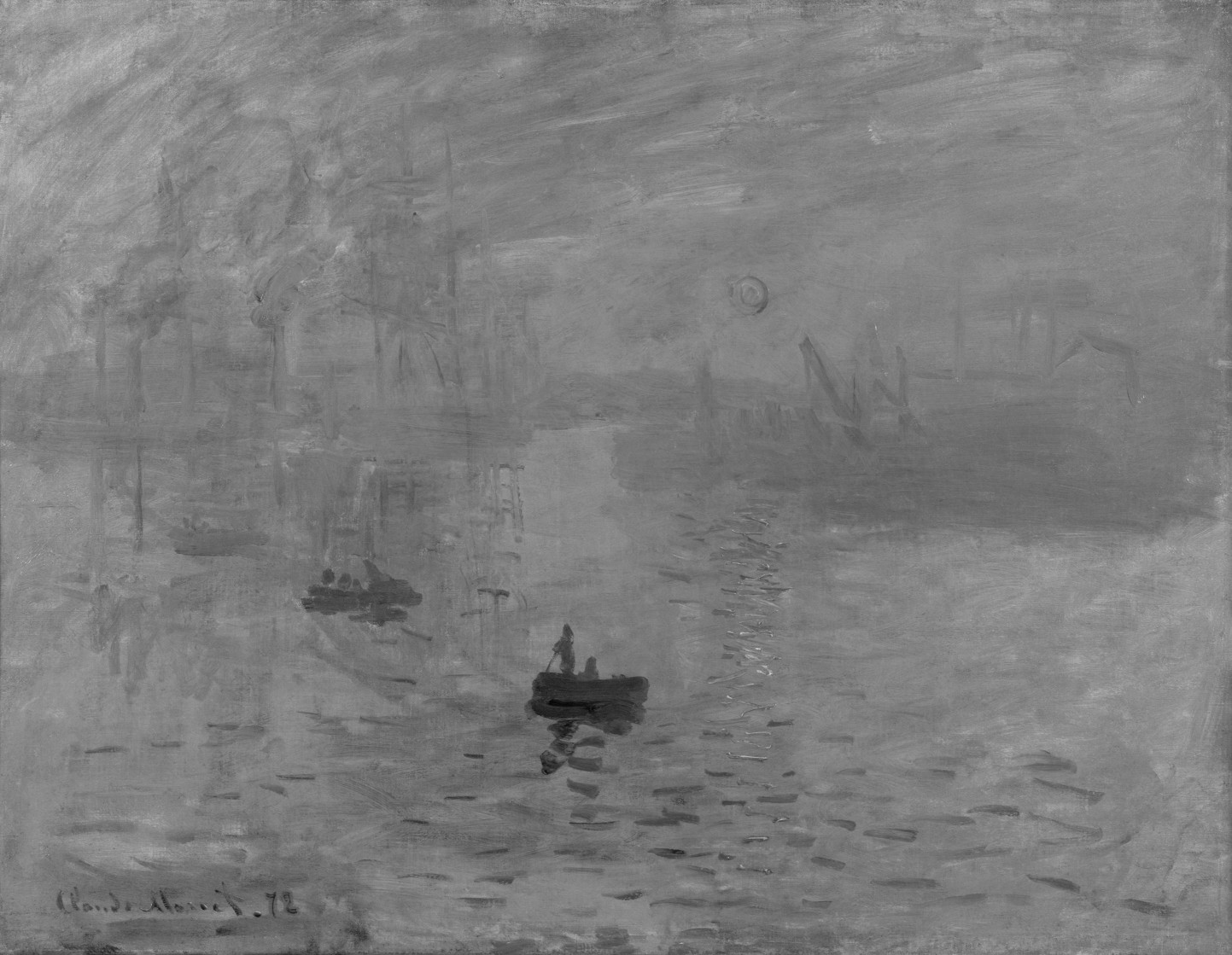

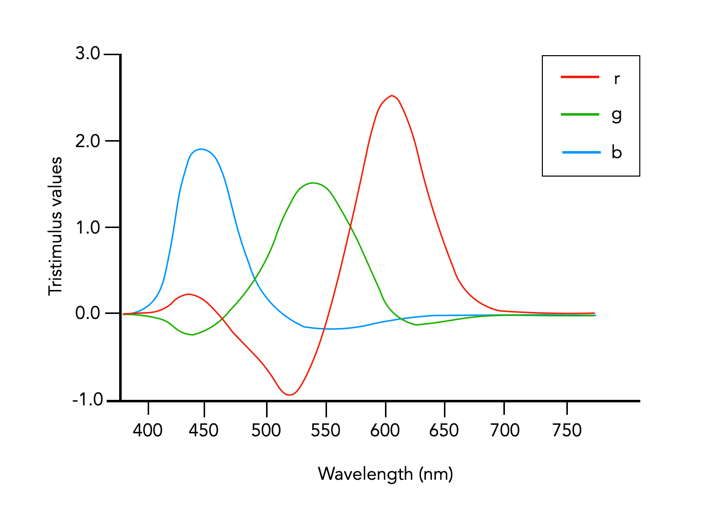

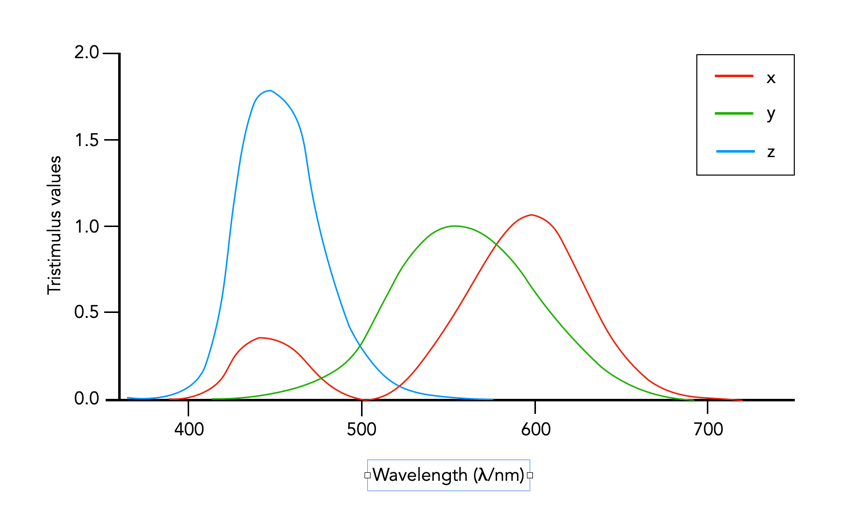

In 1931 CIE amalgamated Wright and Guild’s data and proposed two sets of of colour matching functions: CIE RGB and CIE XYZ. Based on the responses in the experiments, values were plotted to reflect how the average human eye senses the colours in the spectrum, producing three different curves of intensity for each light source to mix all colours of the colour spectrum (Figure 2), i.e. Some of the values for red were negative, and the CIE decided it would be more convenient to work in a colour space where the coefficients were always positive – the XYZ colour matching functions (Figure 3). The new matching functions had certain characteristics: (i) the new functions must always be greater than or equal to zero; (ii) the y function would describe only the luminosity, and (iii) the white-point is where x=y=z=1/3. This produced the CIE XYZ colour space, also known as CIE 1931.

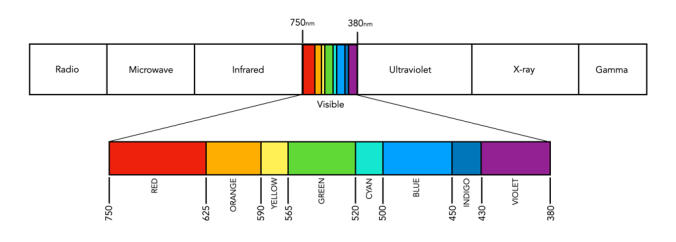

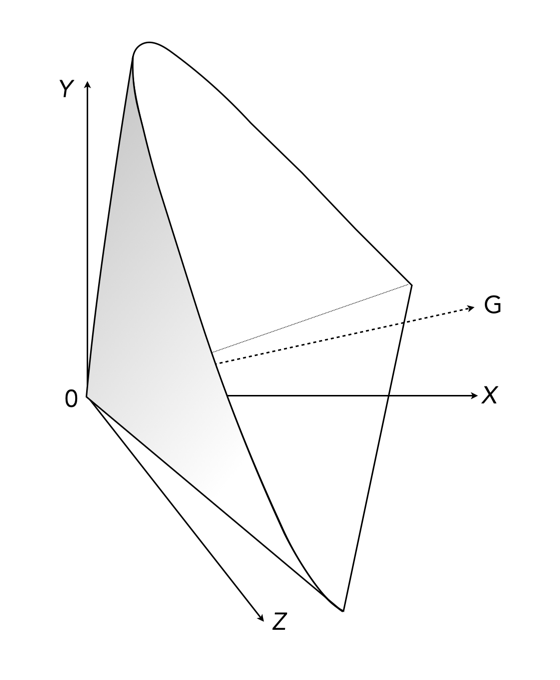

The CIE XYZ colour space defines a quantitative link between distributions of wavelengths in the electromagnetic visible spectrum, and physiologically perceived colours in human colour vision. The space is based on three fictional primary colours, X, Y, and Z, where the Y component corresponds to the luminance (as a measure of perceived brightness) of a colour. All the visible colours reside inside an open cone-shaped region, as shown in Figure 4. CIE XYZ is then a mathematical generalization of the colour portion of the HVS, which allows us to define colours.

The luminance in XYZ space increases along the Y axis, starting at 0, the black point (X=Y=Z=0). The colour hue is independent of the luminance, and hence independent of Y. CIE also defines a means of describing hues and saturation, by defining three normalized coordinates: x, y, and z (where x+y+z=1).

x = X / (X+Y+Z) y = Y / (X+Y+Z) z = Z / (X+Y+Z) z = 1 - x - y

The x and y components can then be taken as the chromaticity coordinates, determining colours for a certain luminance. This system is called CIE xyY, because a colour value is defined by the chromaticity coordinates x and y in addition to the luminance coordinate Y. More on this in the next post on chromaticity diagrams.

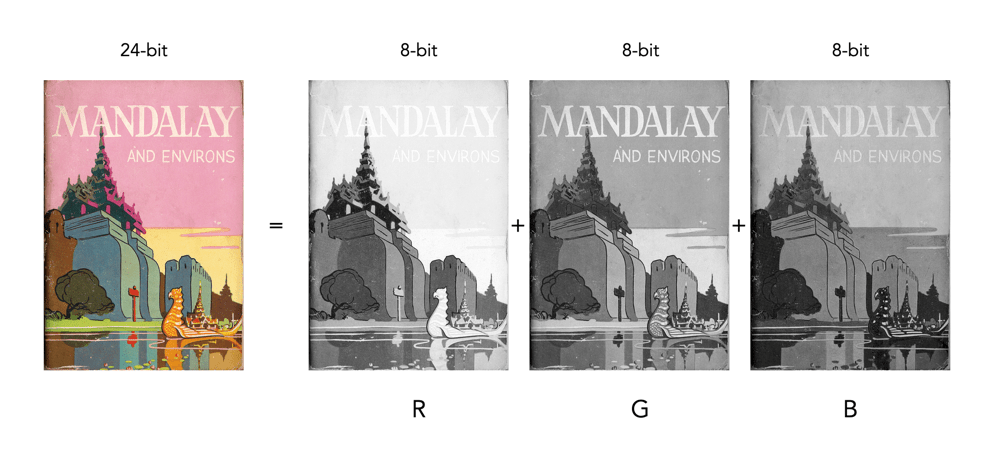

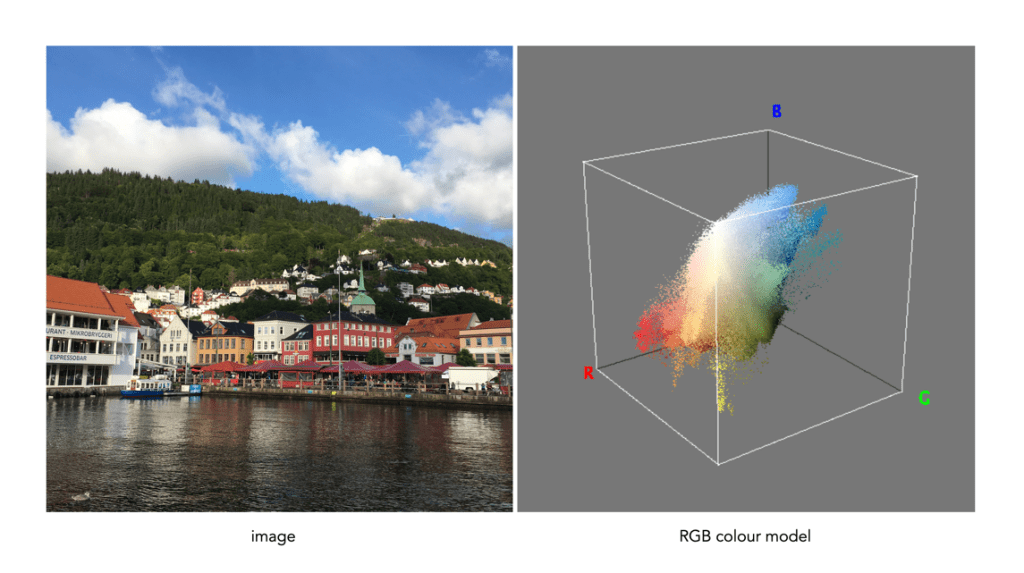

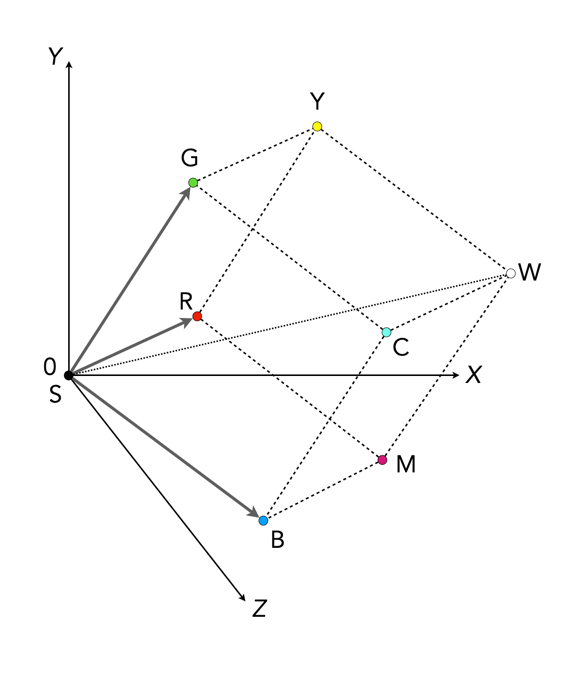

The RGB colour space is related to XYZ space by a linear coordinate transformation. The RGB colour space is embedded in the XYZ space as a distorted cube (see Figure 5). RGB can be mapped onto XYZ using the following set of equations:

X = 0.41847R - 0.09169G - 0.0009209B Y = -0.15866R + 0.25243G - 0.0025498B (luminance) Z = -0.082835R + 0.015708G + 0.17860B

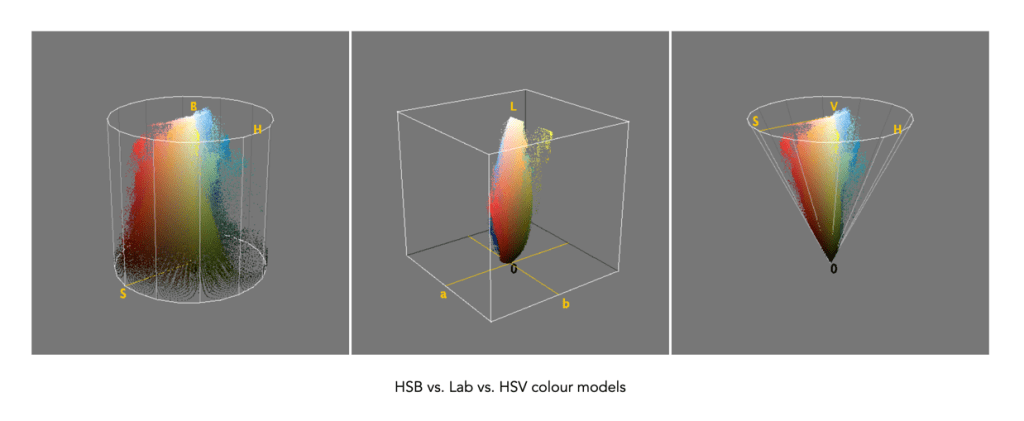

CIEXYZ is non-uniform with respect to human visual perception, i.e. a particular fixed distance in XYZ is not perceived as a uniform colour change throughout the entire colour space. CIE XYZ is often used as an intermediary space in determining a perceptually uniform space such as CIE Lab (or Lab), or CIE LUV (or Luv).

- CIE 1976 CIEL*u*v*, or CIELuv, is an easy to calculate transformation of CIE XYZ which is more perceptually uniform. Luv was created to correct the CIEXYZ distortion by distributing colours approximately proportional to their perceived colour difference.

- CIE 1976 CIEL*a*b*, or CIELab, is a perceptually uniform colour differences and L* lightness parameter has a better correlation to perceived brightness. Lab remaps the visible colours so that they extend equally on two axes. The two colour components a* and b* specify the colour hue and saturation along the green-red and blue-yellow axes respectively.

In 1964 another set of experiments were done allowing for a 10° field of view, and are known as the CIE 1964 supplementary standard colorimetric observer. CIE XYZ is still the most commonly used reference colour space, although it is slowly being pushed to the wayside by CIE1976. There is a lot of information on CIE XYZ and its derivative spaces. The reader interested in how CIE1931 came about in referred to [1,4]. CIELab is the most commonly used CIE colour space for imaging, and the printing industry.

Further Reading

- Fairman, H.S., Brill, M.H., Hemmendinger, H., “How the CIE 1931 color-matching functions were derived from Wright-Guild data”, Color Research and Application, 22(1), pp.11-23, 259 (1997)

- Service, P., The Wright – Guild Experiments and the Development of the CIE 1931 RGB and XYZ Color Spaces (2016)

- Abraham, C., A Beginners Guide to (CIE) Colorimetry

- Zhu, Y., “How the CIE 1931 RGB Color Matching Functions Were Developed from the Initial Color Matching Experiments”.

- Sharma, G. (ed.), Digital Color Imaging Handbook, CRC Press (2003)