Light is the building block of photographs. Luminance describes how much light comes from an object. In a grayscale image, there is only luminance. In many respects it is what provides the “structure” of an image. If no light were to come from an object, an image would appear black. Luminance is one of the primary cues that make you realize you are looking at a three-dimensional object rather than a flat picture.

The human visual system is designed to detect luminosity (light), and chroma (colour). The photoreceptors in human eyes include the cones which handle the chroma and the rods which handle the luminance. Luminance is perceived as different shades of light in grays while chroma are different hues of colour. Colours have intensity while light has brightness. Artists have known for a very long time that colour and luminance can be treated in an artistic sense quite independently. Picasso said, “Colours are only symbols. Reality is to be found in luminance alone.”

When high-luminance colours such as yellow are placed next to low-luminance colours such as dark blue, they create a strong contrast that the visual system interprets as a change in depth. The center-surround effect is also responsible for the optical illusion that colours look different depending on the colour of their surroundings.

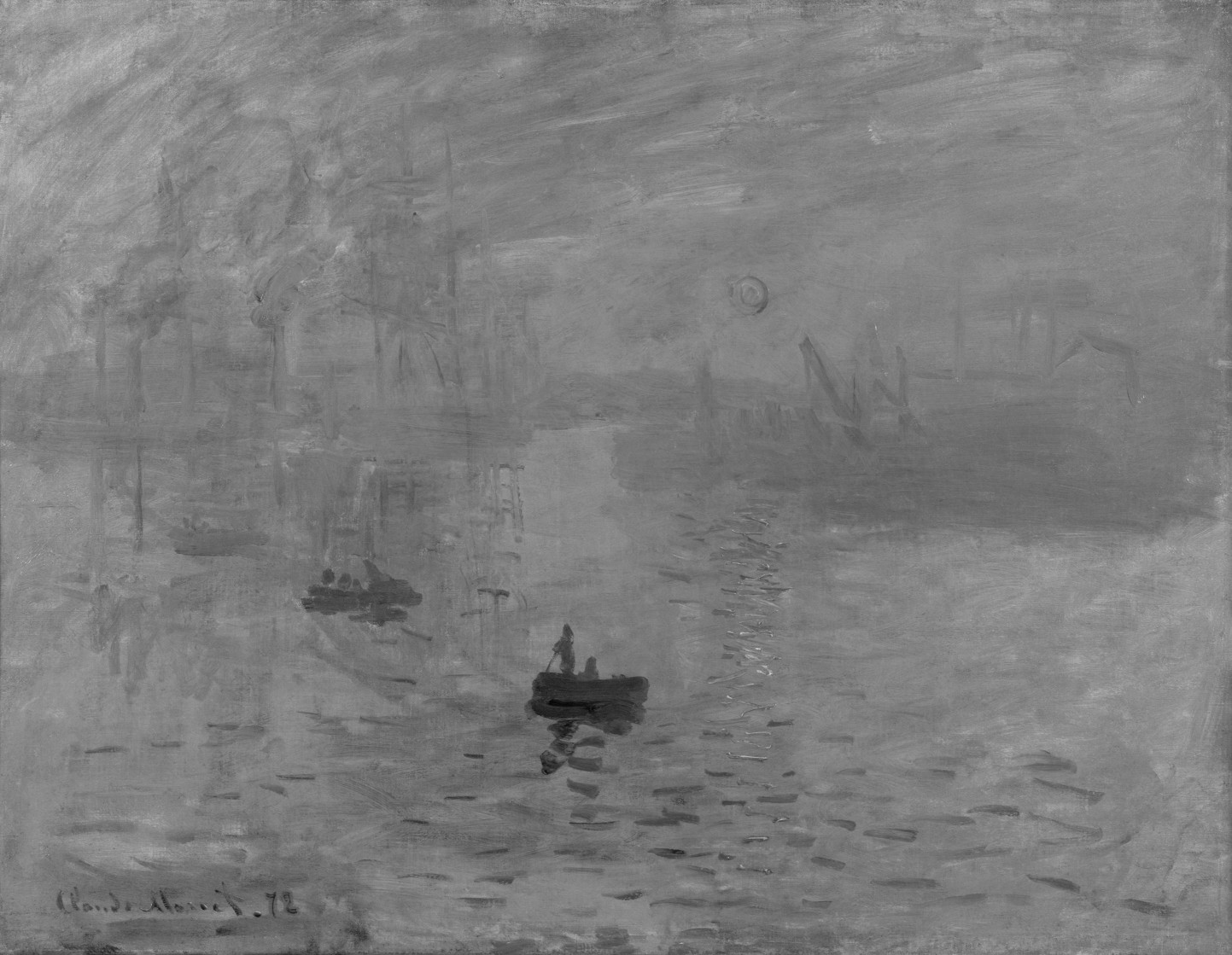

To understand better the interplay of luminance and colour, consider Claude Monet’s 1874 painting, Impression, soleil levant (English Impression, Sunrise), which depicts the the port of Le Havre, France at sunrise.

It would seem as though the rising Sun is the brightest object on the canvas, however when the image is desaturated by removing the colour component, it is shown that the sun, as well as its reflection have the same luminance as the sky – for all intended purposes, disappears. This can be achieved by converting the colour space to HSL, and extracting the Lightness/Luminance component.

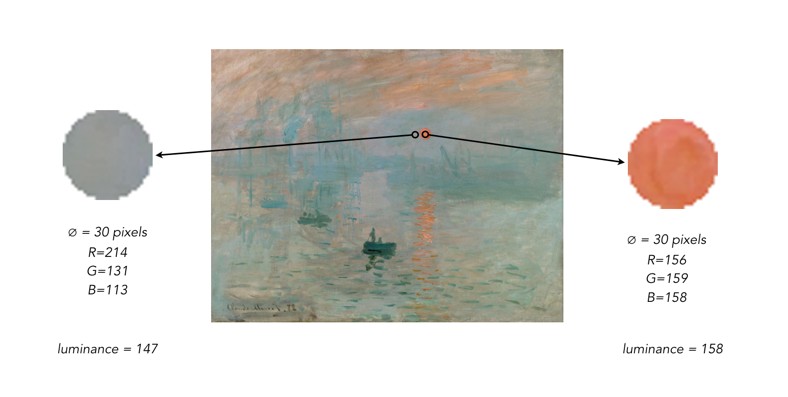

Why? Because Monet used colours which had equal luminance, so the sun blends into the sky. The sun appears brighter because Monet uses a saturated complementary colour to the blue of the sky, so the colours accentuate one another. Without colour, the painting loses some of its meaning. To illustrate this another way, we extracted circles with a diameter of 30 pixels from the sun, and the area adjacent to it. Then the luminance was calculated using the average pixel value found in each extracted region.

The results? Very similar luminance values.