Some people probably wonder why there aren’t any 3D colour histograms. I mean if a colour image is comprised of red, green, and blue components, why not provide those in a combined manner rather than separate 2D histograms or a single 2D histogram with the R,G,B overlaid? Well, it’s not that simple.

A 2D histogram has 256 pieces of information (grayscale). A 24-bit colour image contains 2563 colours in it – that’s 16,777,216 pieces of information. So a three-dimensional “histogram” would contain the same number of elements. Well, it’s not really a histogram, more of a 3D representation of the diversity of colours in the image. Consider the example shown in Figure 1. The sample image contains 428,763 unique colours, representing just 2.5% of all available colours. Two different views of the colour cube (rotated) show the dispersion of colours. Both show the vastness of the 3D space, and conversely the sparsity of the image colour information.

It is extremely hard to create a true 3D histogram. A true 3D histogram would have a count of the number of pixels with a particular RGB triplet at every point. For example, how many times does the colour (23,157,87) occur? It’s hard to visualize this in a 3D sense, because unlike the 2D histogram which displays frequency as the number of occurrences of each grayscale intensity, the same is not possible in 3D. Well it is, kind-of.

In a 3D histogram which already uses the three dimensions to represent R, G, and B, there would have to be a fourth dimension to hold the number of times a colour occurs. To obtain a true 3D histogram, we would have to group the colours into “cells” which are essentially clusters representing similar colours. An example of the frequency-weighted histogram with for the image in Figure 2, using 500 cells, is shown in Figure 2. You can see that while in the colour distribution cube in Figure 1 shows a large band of reds, because these colours exist in the image, the frequency weighted histogram shows that objects with red colours actually comprise a small number of pixels in the image.

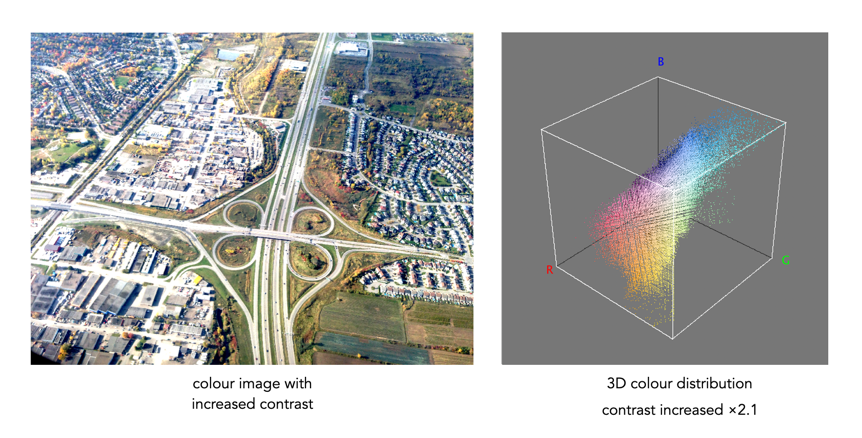

The bigger problem is that it is quite hard to visualize a 3D anything and actively manipulate it. There are very few tools for this. Theoretically it makes sense to deal with 3D data in 3D. The application ImageJ (Fiji) does offer an add-on called Color Inspector 3D, which facilitates viewing and manipulating an image in 3D, in a number of differing colour spaces. Consider another example, shown in Figure 3. The aerial image, taken above Montreal lacks contrast. From the example shown, you can see that the colour image takes up quite a thin band of colours, almost on the black-white diagonal (it has 186,322 uniques colours).

Using the contrast tool provided in ImageJ, it is possible to manipulate the contrast in 3D. Here we have increased the contrast by 2.1 times. You can easily see the result in Figure 4. difference working in 3D makes. This is something that is much harder to do in two dimensions, manipulating each colour independently.

Another example of increasing colour saturation 2 times, and the associated 3D colour distribution is shown in Figure 5. The Color Inspector 3D also allows viewing and manipulating the image in other colour spaces such as HSB and CieLab. For example in HSB the true effect of manipulating saturation can be gauged. The downside is that it does not actually process the full-resolution image, but rather one reduced in size, largely because I imagine it can’t handle the size of the image, and allow manipulation in real-time.