How often do we stop and think about how colour blind people perceive the world around us? For many people there is a reduced ability to perceive colours in the same way that the average person perceives them. Colour blindness, which is also known as colour vision deficiency affects some 8% of males, and 5% of females. Colour blindness means that a person has difficulty seeing red, green, or blue, or certain hues of these colours. In extremely rare cases, a person have an inability to see any colour at all. And one term does not fit all, as there are many differing forms of colour deficiency.

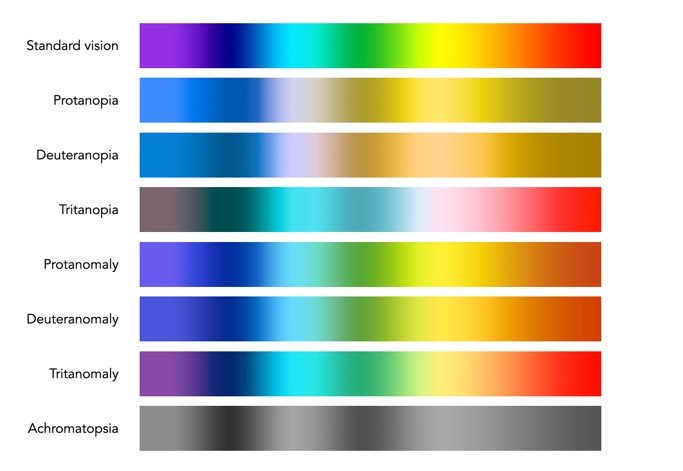

The most common form is red/green colour deficiency, split into two groups:

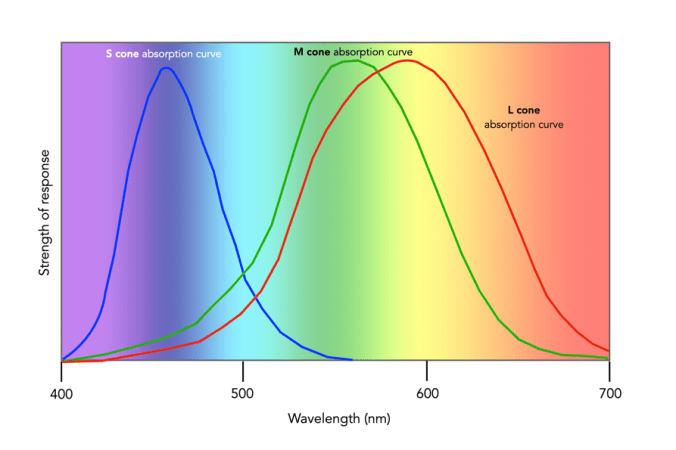

- Deuteranomaly – 3 cones with a reduced sensitivity to green wavelengths. People with deuteranomaly may commonly confuse reds with greens, bright greens with yellows, pale pinks with light grey, and light blues with lilac.

- Protanomaly – The opposite of deuteranomaly, a reduced sensitivity to red wavelengths. People with protanomaly may confuse black with shades of red, some blues with reds or purples, dark brown with dark green, and green with orange.

Then there is also blue/yellow colour deficiency. Tritanomaly is a rare color vision deficiency affecting the sensitivity of the blue cones. People with tritanomaly most commonly confuse blues with greens and yellows with purple or violet.

People with deuteranopia, protanopia, or tritanopia are the dichromatic forms where the associated cones (green, red, or blue) are missing completely. Lastly there is monochromacy, achromatopsia, or total colour blindness are conditions of having mostly defective or non-existent cones, causing a complete lack of ability to distinguish colours.

How does this affect photography? Obviously photographs will be the same, but photographers who have a colour deficiency will perceive a scene differently. For those interested, there are some fine articles on how photographers deal with colourblindness.

- Check here for an exceptional article on how photographer Cameron Bushong approaches colour deficiency.

- Photographer David Wilder offers some insights into working on location and some tips for editing.

- David Wilder describes taking photographs in Iceland using special glasses which facilitate the perception of colour.

- Some examples of what the world looks like when your colour-blind.

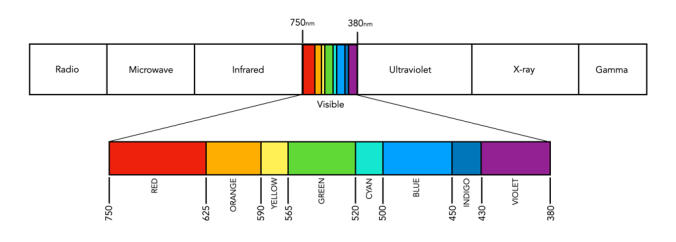

Below is a rendition of the standard colour spectrum as it relates to differing types of colour deficiency.

In reality people who are colourblind may be better at discerning some things. A 2005 article [1] suggests people with deuteranomaly may actually have an expanded colour space in certain circumstances, making it possible for them to for example discern subtle shades of khaki.

Note: The colour deficiencies shown above were simulated using ImageJ’s (Fiji) “Simulate Color Blindness” function. An good online simulator is the Coblis, Color Blindness Simulator.

- Bosten, J.M., Robinson, J.D., Jordan, G., Mollon, J.D., “Multidimensional scaling reveals a color dimension unique to ‘color-deficient’ observers“, Current Biology, 15(23), pp.R950-R952 (2005)