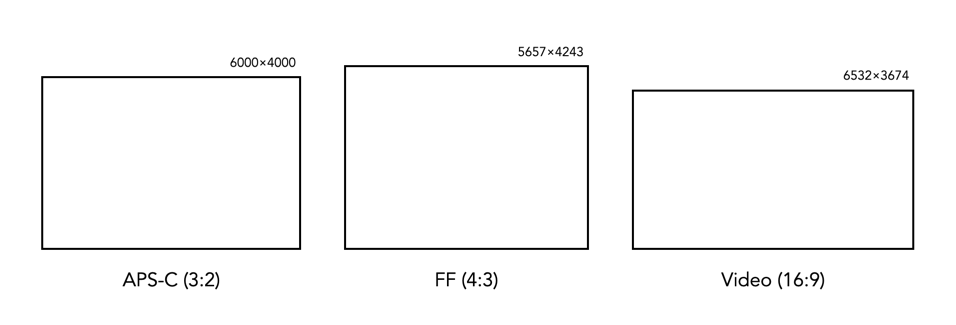

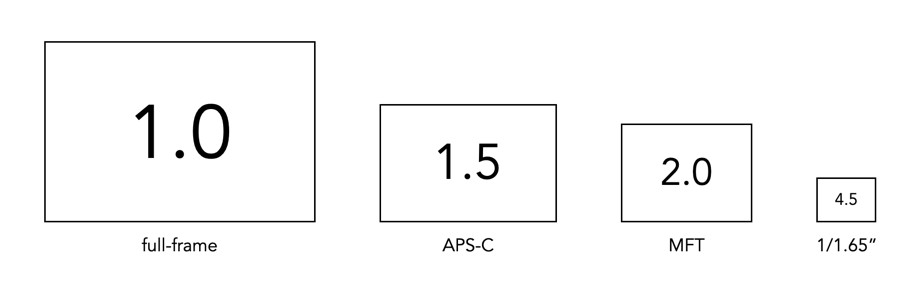

There is a lot of talk on the internet about the “equivalency” of crop-sensors relative to full-frame sensors – often in an attempt to somehow rationalize things in the context of the ubiquitous 35mm film frame size (36×24mm). Usually equivalence involves the use of the cringe-worthy “crop-factor”, which is just a numeric value which compares the dimensions of one sensor against those of another. For example a camera with an APS-C sensor, e.g. Fuji-X, has a sensor size of 23.5×15.6mm which when compared with a full-frame (FF) sensor gives a crop-factor of approximately 1.5. The crop-factor is calculated by dividing the diagonal of the FF sensor by that of the crop-sensor, in the case of the example 43.42/28.21 = 1.53.

Easy right? But this only really only matters if you want to know what the full-frame equivalent of a crop-sensor lens is. For example a 35mm lens has an angle of view of rough 37° (horizontal). If you want to compare this to a full-frame lens, you can multiply this by the crop-factor for APS-C sensors, so 35×1.5≈52.5mm. So an APS-C 35mm lens has a full-frame equivalency of 52.5mm which can be rounded to 50mm, the closest full-frame equivalent lens. Another reason equivalency might be important is perhaps you want to take similar looking photographs with two different cameras, i.e. two cameras with differing sensor sizes.

But these are the only real contexts where it is important – regardless of the sensor size, if you are not interested in comparing the sensor to that of a full-frame camera, equivalencies don’t matter. But what does equivalence mean? Well it has a number of contexts. Firstly there is the most commonly used situation – focal-length equivalence. This is most commonly used to relate how a lens attached to a crop-sensor camera behaves in terms of a full-frame sensor. It can be derived using the following equation:

Equivalent-FL = focal-length × crop-factor

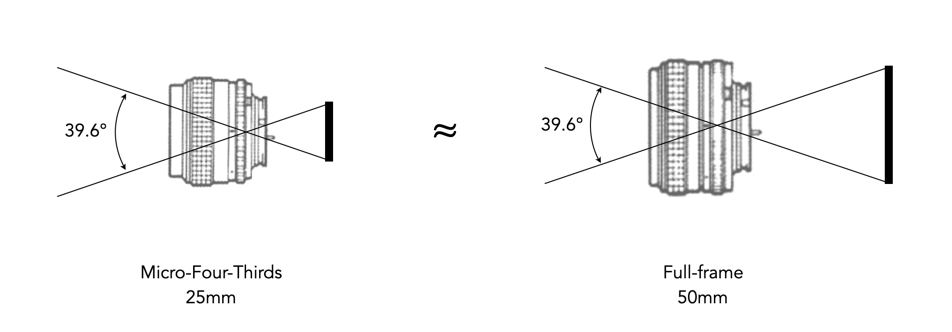

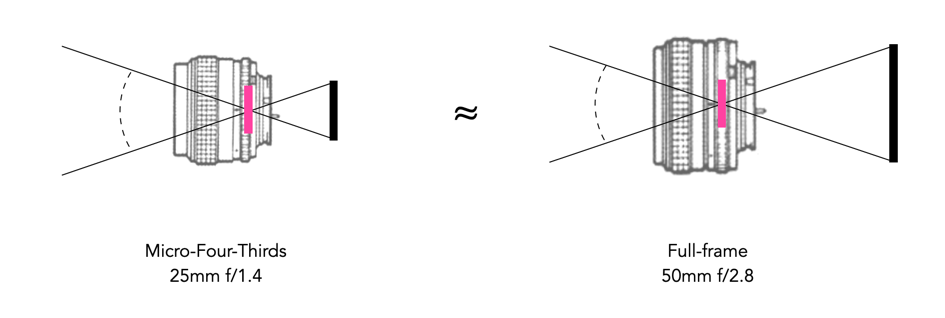

The crop-factor in any case is more of a differential-factor which can be used to compare lenses on different sized sensors. Figure 2 illustrates two different systems with different sensor sizes, with two lenses that have an identical angle of view. To achieve the same angle of view on differently sized sensors, a different focal length is needed. A 25mm lens on a MFT sensor with a crop-factor of 2.0 gives the equivalent angle of view as a 50mm lens on a full-frame sensor.

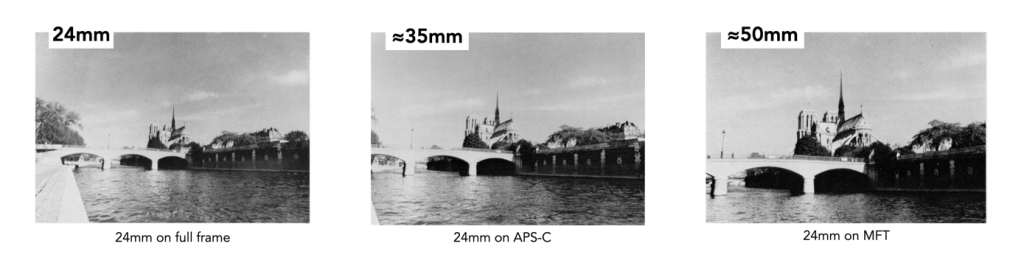

Focal length equivalency really just describes how a lens will behave on different sized sensors, with respect to angle-of-view (AOV). For example the image below illustrates the AOV photograph obtained when using a 24mm lens on three different sensors. A 24mm lens used on an APS-C sensor would produce an image equivalent to a full-frame 35mm lens, and the same lens used on a MFT sensor would produce an image equivalent to a full-frame 50mm lens.

When comparing a crop-sensor camera directly against a FF camera, in the context of reproducing a particular photograph, two other equivalencies come into play. The first is aperture equivalence. An aperture is just the size of the hole in the lens diaphragm that allows light to pass through. For example an aperture of f/1.4 on a 50mm lens means a maximum aperture size of 50mm/1.4 = 35.7mm. A 25mm f/1.8 MFT lens will not be equivalent to a 50mm f/1.8mm FF lens because the hole on the FF lens would be larger. To make the lenses equivalent from the perspective of aperture requires multiplying the aperture value by a crop factor:

Equivalent-Aperture = f-number × crop-factor

Figure 4 illustrates this – a 25mm lens used at f/1.4 on a MFT camera would be equivalent to using a 50mm with an aperture of f/2.8 on a full-frame camera.

The second is ISO equivalence, with a slightly more complication equation:

Equivalent-ISO = ISO × crop-factor²

Therefore a 35mm APS-C lens at f/5.6 and 800 ISO would be equivalent to a 50mm full frame lens at f/8 and 1800 ISO. Below is a sample set of equivalencies:

Focal Length / F-stop = Aperture ∅ (ISO)

MFT (×2.0): 25mm / f/2.8 = 8.9mm (200)

APS-C (×1.5): 35mm / f/3.9 = 8.9mm (355)

Full-frame (×1.0): 50mm / f/5.6 = 8.9mm (800)

6×6 (×0.55): 90mm / f/10.0 = 9.0mm (2600)

Confused? Yes, and so are many people. None of this is really that important, except to understand how a lens behaves will be different depending on the size of the sensor in the camera it is used on. Sometimes, focal-length equivalence isn’t even possible. There are full-frame lenses that just don’t have a cropped equivalent. For example a Sigma 14mm f/1.8 would need an APS-C equivalent of 9mm f/1.2, or a MFT equivalent of 7mm f/0.9. The bottom line is that if you only photography using a camera with an APS-C sensor, then how a 50mm lens behaves on that camera should be all that matters.