“Through absence of color, three-dimensionality and motion, the black-and-white photography is ipso facto ‘unnatural’. It expresses reality symbolically: gray tone values instead of color, two-dimensional projection (perspective) instead of space, blurredness or single-phase instead of constant motion. It is ‘symbolic’ in the same sense that speech and writing are, where sounds (words) are symbols for objects and conceptions, and signs (letters) are symbols for sounds (words). Photography means ‘reproduction’ only in the rare cases where the rendering of a two-dimensional, black-and-white object is the aim; otherwise it must be called a translation.”

Andreas Feininger, Feininger on Photography (1949, pp.195-196)

black and white

32 shades of gray

Humans don’t interpret gray tones very well – the human visual system perceiving approximately 32 shades of gray. So an 8-bit image with 256 tones already contains too much information for humans to interpret. That’s why you don’t really see any more clarity in a 10-bit image with 1024 shades of gray than a 5-bit image with 32 shades of gray. But why do we only see approximately 32 shades of gray?

It is the responsibility of the rod receptors to deal with black and white. The rods are far less precise than the cones which deal with colour, but are more sensitive to low levels of light that are typically associated with being able to see in a dimly lit room, or at night. There are supposedly over 100 million rods in the retina, but this doesn’t help distinguish any more than 30-32 shades of gray. This may stem from evolutionary needs – in the natural world there are very few things that are actually gray – stones, some trunks of trees, weathered wood, so there was very little need to distinguish between more than a few shades of gray. From an evolutionary perspective, humans needed night vision because they lived half their lives in darkness. This advantage remained crucial, apart perhaps form the past 150 years or so.

The rods work so well that dark adapted humans can detect just a handful of photons hitting the retina. It is likely this is the reason there are so many rods in the retina – so that in exceedingly low levels of light as many as possible of the scarce photons are captured by rods. Figure 1 illustrates two grayscale optical illusions, which rely on our eyes insensitivity to shades of gray. In the image on the left, the horizontal strip of gray is actually the same shade throughout, although our eyes deceive us into thinking that it is light on the left and dark on the right. in the image on the right, the inner boxes are all the same shade of gray, even though they appear to be different.

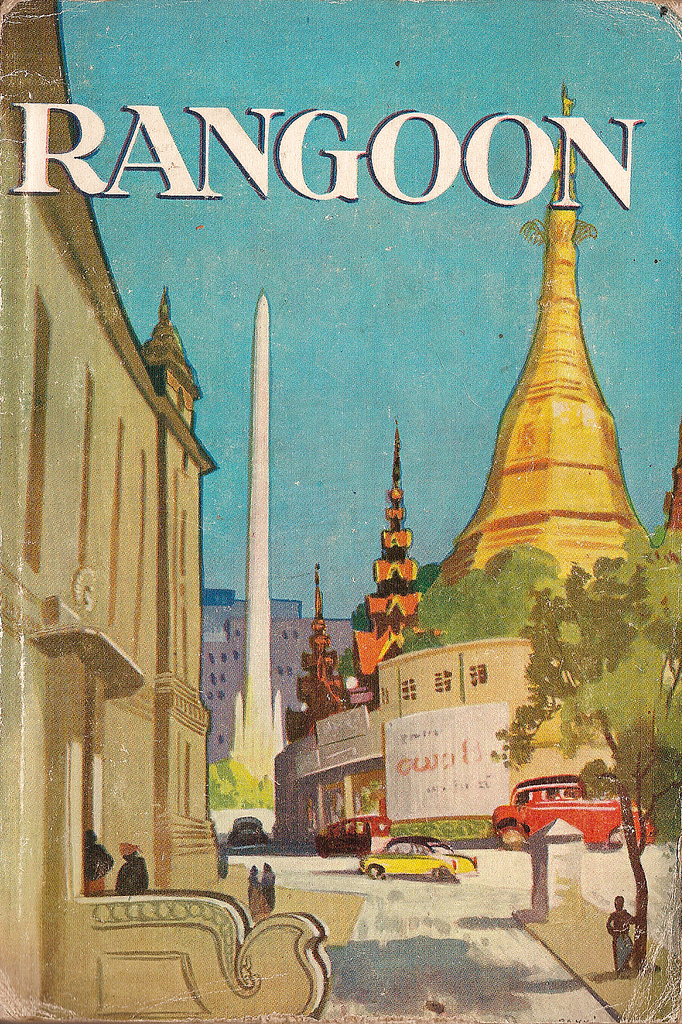

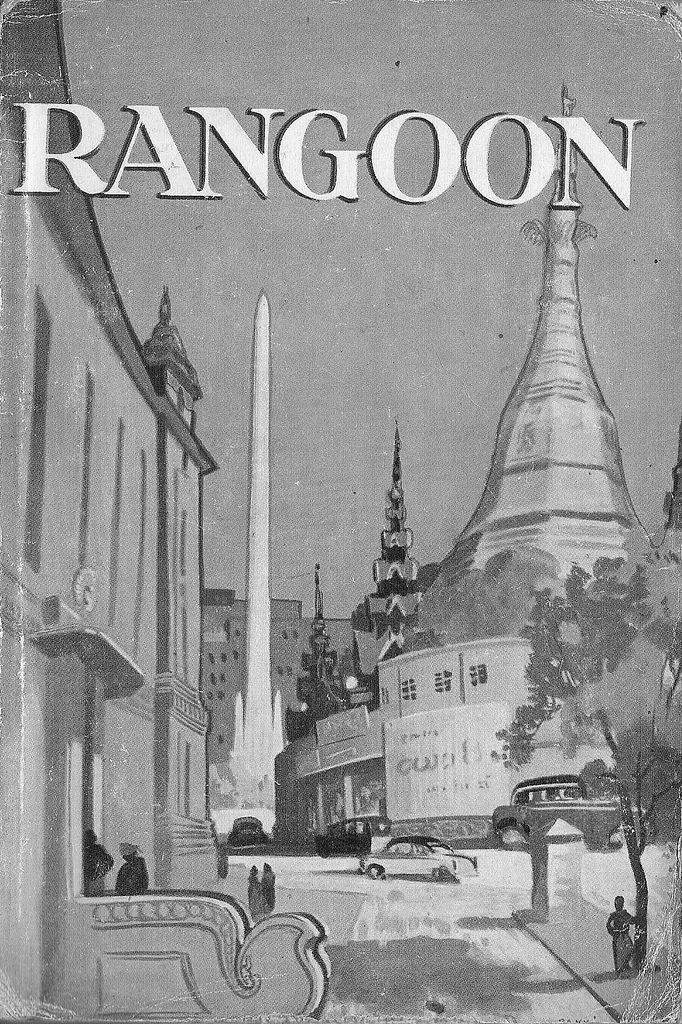

To illustrate this further, consider the series of images in the figure below. The first image is the original colour image. The middle image shows that image converted to grayscale with 256 shades of gray. The image on the right shows the colour image converted to 4-bit grayscale, i.e. 16 shades of gray. Is there any perceptual difference between Fig.2b and 2c? Hardly.

You will see articles that suggest humans can see anywhere from 500-750 shades of gray. They are usually articles related to radiology, where radiologists interpret images like x-rays. The machines that take these medical images are capable of producing 10-bit or 12-bit images which are interpreted on systems capable of improving contrast. There may of course be people that can see more shades of gray, just like there are people with a condition called aphakia that possess ultraviolet vision (aphakia is a lack of a lens which normally blocks UV light, so they are able to perceive wavelengths up to 300nm). There are also tetrachromats who posses a fourth cone cell, allowing them to see up to 100 million colours.

The simplicity of achromatic photographs

We live in a world where colour surrounds us, so why would anyone want to take an achromatic, black-and-white photograph? What draws us to a B&W photograph? Many modern colour images are brightened to add a sense of the exotic in the same way that B&W invokes an air of nostalgia. B&W does not exaggerate the truth in the same way that colour does. It does sometimes veil the truth, but in many ways it is an equalizer. Colours and the emotions they represent are stripped away, leaving nothing but raw structure. We are then less likely to draw emotions into the interpretation of achromatic photographs. There is a certain rawness to B&W photographs, which cannot be captured by colour.

Every colour image is of course built upon an achromatic image. The tonal attributes provides the structure, the chrominance the aesthetic elements that help us interpret what we see. Black and white photographs offer simplicity. When colour is removed from a photograph, it forces a different perspective of the world. To create a pure achromatic photograph means the photographer has to look beyond the story posed by the chromatic elements of the scene. It forces one to focus on the image. There is no hue, no saturation to distract. The composition of the scene suddenly becomes more important. Both light and the darkness of shadows become more pronounced. The photographic framework of a world without colour forces one to see things differently. Instead of highlighting colour, it helps highlight shape, texture, form and pattern.

Sometimes even converting a colour image to B&W using a filter can make the image content seem more meaningful. Colour casts or odd-ball lighting can often be vanquished if the image is converted. Noise that would appear distracting in a colour image, adds to an image as “grain” in B&W. B&W images will always capture the truth of a subjects structure, but colours are always open to interpretation due to the way individuals perceive colour.

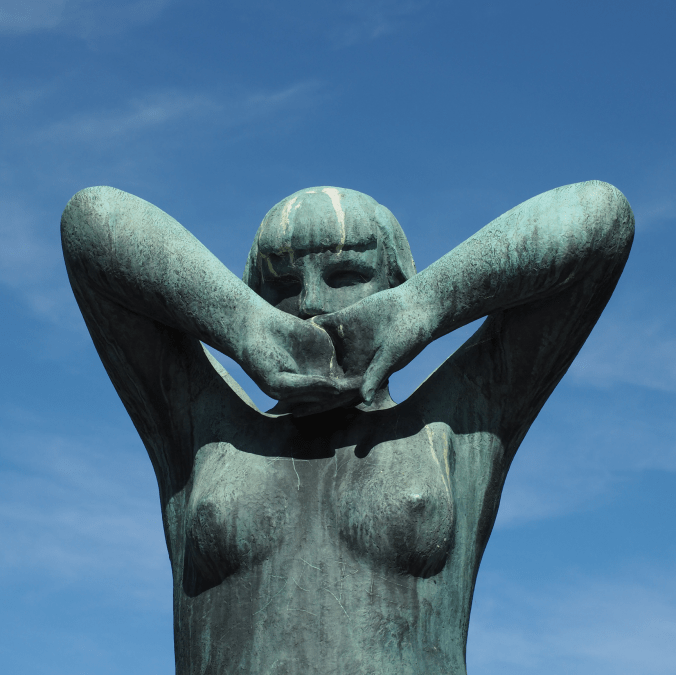

Above is a colour photograph of a bronze sculpture taken at The Vigeland Park in Oslo, a sculpture park displaying the works of Gustav Vigeland. The colour image is interesting, but the viewer is somewhat distracted by the blue sky, and even the patina on the statue. A more interesting take is the achromatic image, obtained via the Instagram Inkwell filter. The loss of colour has helped improve the contrast between the sculpture and its background.

Are black-and-white photographs really black and white?

Black-and-white photography is somewhat of a strange term, because it alludes to the fact that the photograph is black-AND-white. However black-and-white photographs if interpreted correctly would mean an image which contains only black and white (in digital imaging terms a binary image). Alternatively they are sometimes called monochromatic photographs, but that too is a broad term, literally meaning “all colours of a single hue“. This means that cyanotype and sepia-tone prints, are also to be termed monochromatic. A colour image that contains predominantly bright and dark variants of the same hue could also be considered monochromatic.

Using the term black-and-white is therefore somewhat of a misnomer. The correct term might be grayscale, or gray-tone photographs. Prior to the introduction of colour films, B&W film had no designation, it was just called film. With the introduction of colour film, a new term had to be created to differentiate the types of film. Many companies opted for the use terms like panchromatic, which is an oddity because the term means “sensitive to all visible colors of the spectrum“. However in the context of black-and-white films, it implies a B&W photographic emulsion that is sensitive to all wavelengths of visible light. Afga produced IsoPan and AgfaPan, and Kodak Panatomic. Differentially, colour films usually had the term “chrome” in their names.

All these terms have one thing in common, they represent the shades of gray across the full spectrum from light to dark. In the digital realm, an 8-bit grayscale image has 256 “shades” of gray, from 0 (black) to 255 (white). A 10-bit grayscale image has 1024 shades, from 0→1023. The black-and-white image shown in Fig.1 illustrates quite aptly an 8-bit grayscale image. But grays are colours as well, albeit without chroma, so they would be better termed achromatic colours. It’s tricky because a colour is “a visible light with a specific wavelength”, and neither black nor white are colours because they do not have specific wavelengths. White contains all wavelengths of visible light and black is the absence of visible light. Ironically, true blacks and true whites are rare in photographs. For example the image shown in Fig.1 only contains grayscale values ranging from 24..222, with few if any blacks or whites. We perceive it as a black-and-white photograph only because of our association with that term.

Does a lack of colour make it harder to extract the true context of pictures?

For many decades, achromatic black-and-white (B&W) photographs were accepted as the standard photographic representation of reality. That is until the realization of colour photography for the masses. Kodak introduced Kodachrome in 1936 and Ektachrome in the 1940s which lead to the gradual, popular adoption of colour photography. It only became practical for everyday photographers during the mid-1950s after film manufacturers had invented processes that made colour pictures sufficiently easy to develop. That didn’t mean that B&W disappeared from society, as in certain fields like journalistic photography they remained the norm. There were a number of reasons for this – news photos were generally printed in B&W, and B&W film was faster, meaning less light was needed to take an image, allowing photojournalists to shoot in a variety of conditions. So from a journalistic viewpoint, people interpreted the news of the world in B&W for nearly a century.

The difference between B&W and colour is that humans don’t see the world in monochromatic terms. Humans have the potential to discern millions of colours, and yet are limited to approximately 32 shades of gray. We have evolved in this manner because the world around us is not monochromatic, and our very survival once depended on our ability to separate good food from the not so good. Many things can be inferred from colour. Many things are lost in B&W. Colour catches the eye, and highlights regions of interest. For instance, setting and time of day/year can be inferred from a photograph’s colours. Mood can also be communicated based on colour.

Black-and-white photographs offer a translation of our view of the world into a unique achromatic medium. Shooting B&W photographs is clearly more challenging because unlike the 16 million odd colours available to describe a scene, B&W typically offers only 256, from pure black (0), to pure white (255). Take for example a photograph taken during the First World War. These photographs were typically B&W, and grainy, painting a rather grim picture of all aspects of society during this period. We typically associated B&W with nostalgia. There was some colour photography during the early 20th century, provided by the Autochrome Lumière technology, and resulting in some 72,000 photographs of the time period from places all over the world. But seeing things in B&W means having to interpret a scene without the advantage of colour. Consider the following photograph from Paris during the early 1900s. It offers a very vibrant rendition of the street scene, with the eye drawn to the varied colour posters on the wall of the building.

Without the colour, we are left with a somewhat drab and gloomy scene, befitting the somber mood associated with the early years of the early 20th century. In the B&W we cannot see the colour of the posters festooning the buildings. What is interesting is that we are likely not use to seeing colour photographs from before the 1950s. It’s almost like we expect images from the before 1950 to be monochromatic, maybe because we perceive these years filled with hardship and suffering. But there is something unique about the monochrome domain.

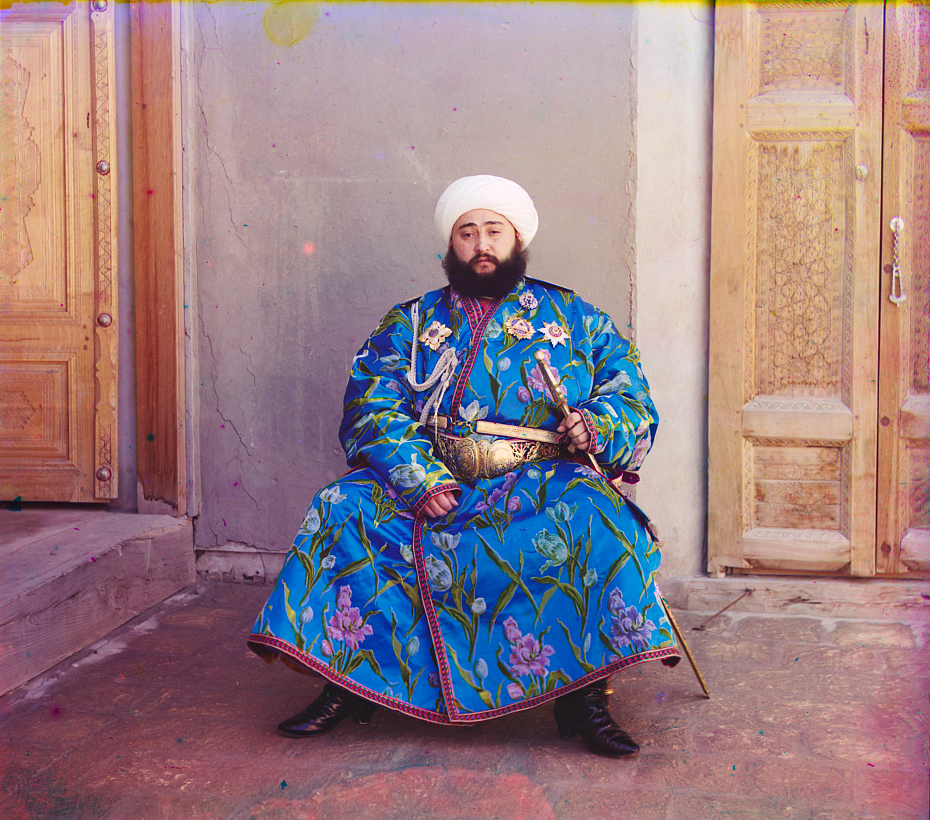

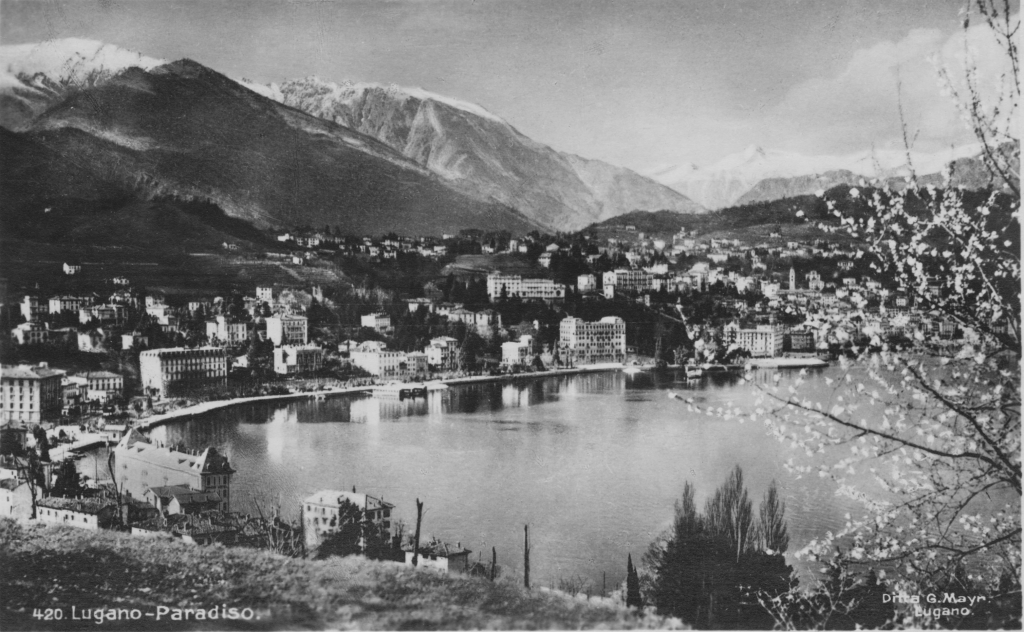

The aesthetic of black-and-white photographs is based on many factors, including lighting, any colour filters that were used during acquisition of the photograph, and the colour sensitivity of the B&W film. Sergei Mikhailovich Prokudin-Gorskii (1863-1944) was a man well ahead of his time. He developed an early technique for taking colour photographs involving a series of monochrome photographs and colour (R-G-B) filters. The images below show an example of Alim Khan, Emir of Bukhara. It is shown in comparison with two grayscale renditions of the photograph. The first is the lightness component from the Lab colour space, and the second is a grayscale image extracted from RGB using G=0.299R+0.587G+0.114B. Both offer a different perspective of how the colour in the image could be rendered by the camera. None present the vibrance of the image in the same way as the colour image.

How do we perceive photographs?

Pictures are flat objects that contain pigment (either colour, or monochrome), and are very different from the objects and scenes they represent. Of course pictures must be something like the objects they depict, otherwise they could not adequately represent them. Let’s consider depth in a picture. In a picture, it is often easy to find cues relating to the depth of a scene. The depth-of-field often manifests itself as a region of increasing out-of-focus away from the object which is in focus. Other possibilities are parallel lines than converge in the distance, e.g. railway tracks, or objects that are blocked by closer objects. Real scenes do not always offer such depth cues, as we perceive “everything” in focus, and railway tracks do not converge to a point! In this sense, pictures are very dissimilar to the real world.

If you move while taking a picture, the scene will change. Objects that are near move more in the field-of-view than those that are far away. As the photographer moves, so too does the scene, as a whole. Take a picture from a moving vehicle, and the near scene will be blurred, the far not as much, regardless of the speed (motion parallax). This then is an example of a picture for which there is no real world scene.

Photography then, is not about capturing “reality”, but rather capturing our perception, our interpretation of the world around us. It is still a visual representation of a “moment in time”, but not one that necessarily represents the world around us accurately. All perceptions of the world are unique, as humans are individual beings, with their own quirks and interpretations of the world. There are also things that we can’t perceive. Humans experience sight through the visible spectrum, but UV light exists, and some animals, such as reindeer are believed to be able to see in UV.

So what do we perceive in a photograph?

Every photograph, no matter how painstaking the observation of the photographer or how long the actual exposure, is essentially a snapshot; it is an attempt to penetrate and capture the unique esthetic moment that singles itself out of the thousands of chance compositions, uncrystallized and insignificant, that occur in the course of a day.

Lewis Mumford, Technics and Civilization (1934)