Black-and-white photography is somewhat of a strange term, because it alludes to the fact that the photograph is black-AND-white. However black-and-white photographs if interpreted correctly would mean an image which contains only black and white (in digital imaging terms a binary image). Alternatively they are sometimes called monochromatic photographs, but that too is a broad term, literally meaning “all colours of a single hue“. This means that cyanotype and sepia-tone prints, are also to be termed monochromatic. A colour image that contains predominantly bright and dark variants of the same hue could also be considered monochromatic.

Using the term black-and-white is therefore somewhat of a misnomer. The correct term might be grayscale, or gray-tone photographs. Prior to the introduction of colour films, B&W film had no designation, it was just called film. With the introduction of colour film, a new term had to be created to differentiate the types of film. Many companies opted for the use terms like panchromatic, which is an oddity because the term means “sensitive to all visible colors of the spectrum“. However in the context of black-and-white films, it implies a B&W photographic emulsion that is sensitive to all wavelengths of visible light. Afga produced IsoPan and AgfaPan, and Kodak Panatomic. Differentially, colour films usually had the term “chrome” in their names.

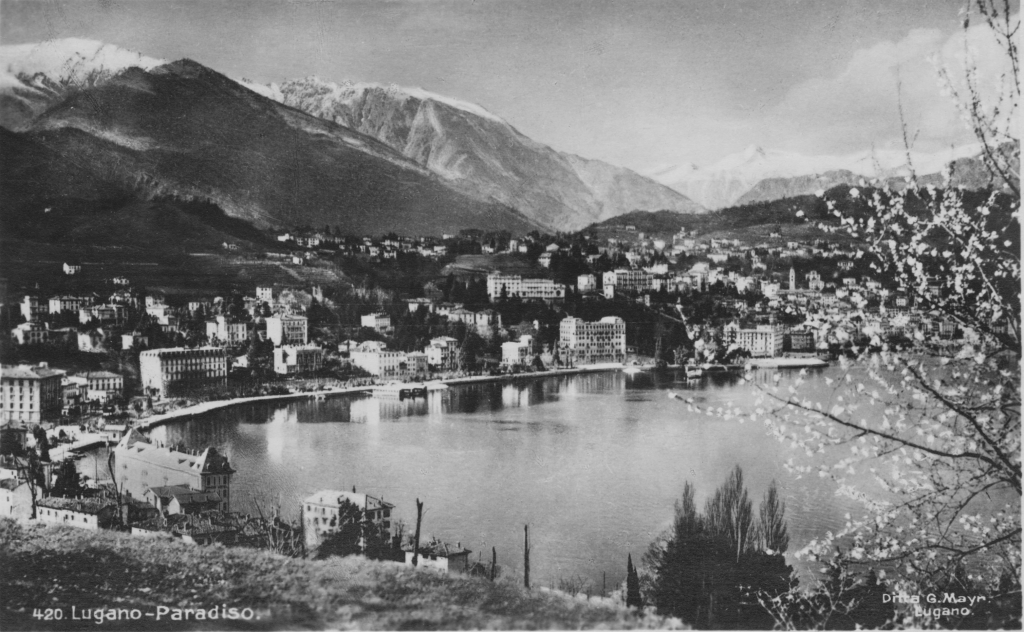

All these terms have one thing in common, they represent the shades of gray across the full spectrum from light to dark. In the digital realm, an 8-bit grayscale image has 256 “shades” of gray, from 0 (black) to 255 (white). A 10-bit grayscale image has 1024 shades, from 0→1023. The black-and-white image shown in Fig.1 illustrates quite aptly an 8-bit grayscale image. But grays are colours as well, albeit without chroma, so they would be better termed achromatic colours. It’s tricky because a colour is “a visible light with a specific wavelength”, and neither black nor white are colours because they do not have specific wavelengths. White contains all wavelengths of visible light and black is the absence of visible light. Ironically, true blacks and true whites are rare in photographs. For example the image shown in Fig.1 only contains grayscale values ranging from 24..222, with few if any blacks or whites. We perceive it as a black-and-white photograph only because of our association with that term.