Artistic movements don’t arise out of a void. There are many factors which have contributed to the changes in Japanese society. Following World War 2 Japan was occupied by the United States, leading to the introduction of Western popular culture and consumerism, which was aptly termed Americanization. The blend of modernity and tradition was likely to lead to some waves, which was magnified by the turbulent changes occurring in Western society in the late 1960s, e.g. the demonstrations against the Vietnam War. In the late 1960s, Japan’s rapid economic growth began to falter, exposing a fundamental opposition to Japan’s postwar political, economic and cultural structure, which lead to a storm of protests by the likes of students and farmers.

It had a long-term effect on photography, forcing a rethink on how it was perceived. In November 1968 a small magazine called Provoke was published, conceived by art critic Koji Taki (1928-2011) and photographer Takuma Nakahira, with poet Takahiko Okada (1939-1997) and photographer Yutaka Takanashi as dojin members. Daido Moriyama joined a for the second and third issues, bringing with him his early influences of Cartier-Bresson. The subtitle for the magazine was “Provocative Materials for Thought”, and each issue was composed of photographs, essays and poems. The magazine had a lifespan of three issues, the Provoke members disbanding due to a lack of cohesion in their ideals.

The ambitious mission of Provoke to create a new photographic language that could transcend the limitations of the written word was declared with the launch of the magazine’s first issue. The year was 1968 and Japan, like America, was undergoing sweeping changes in its social structure.

Russet Lederman, 2012

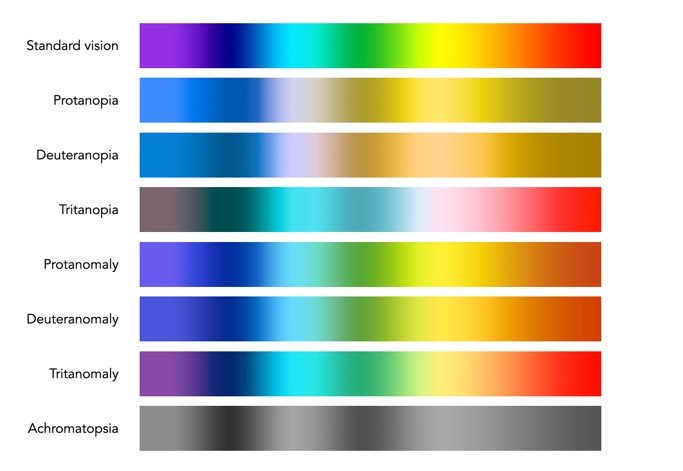

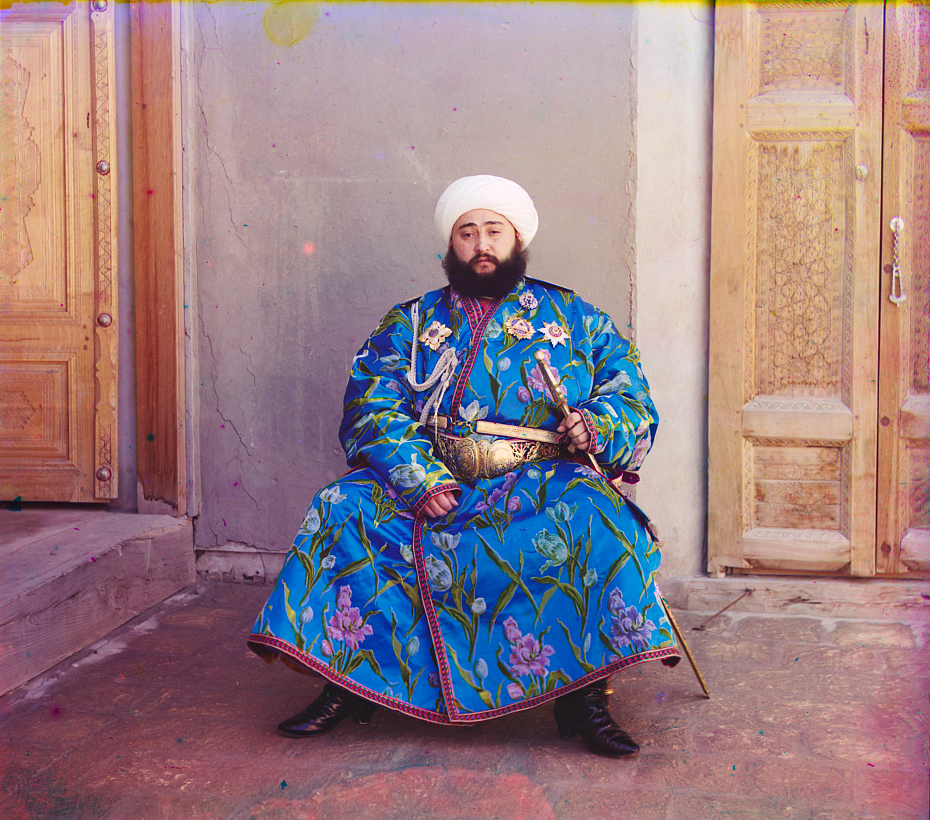

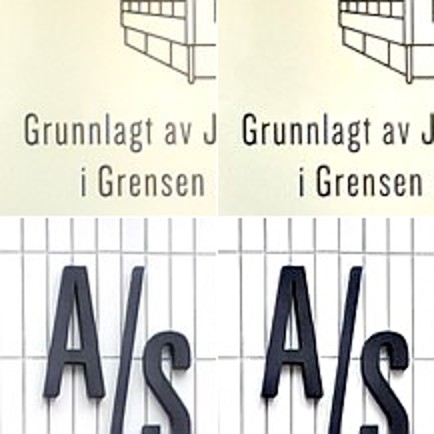

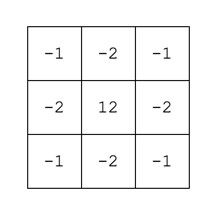

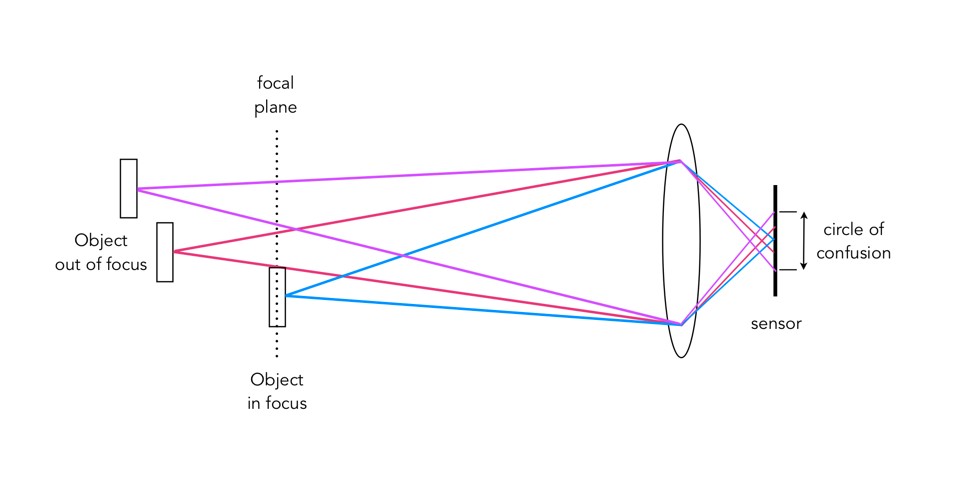

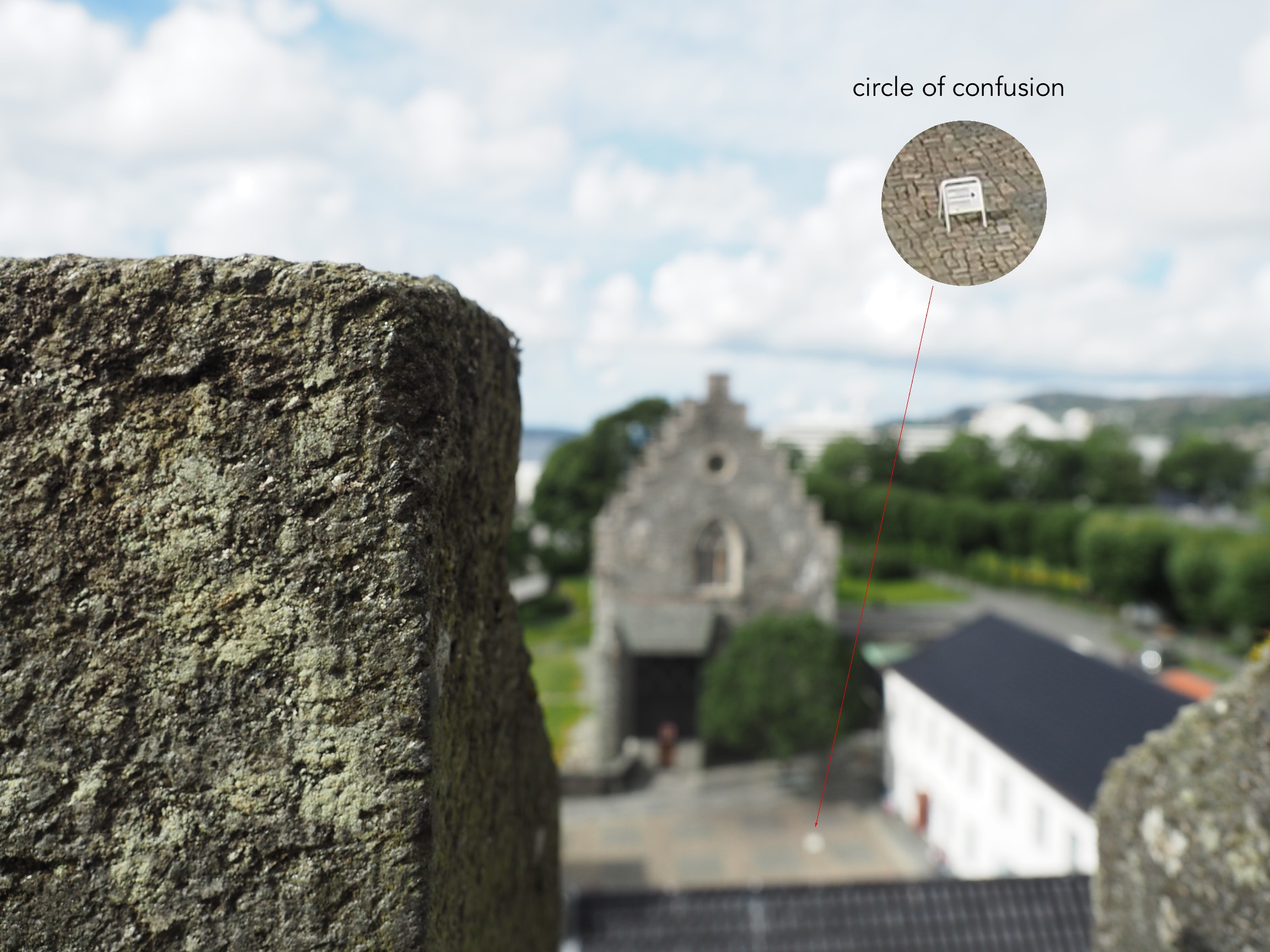

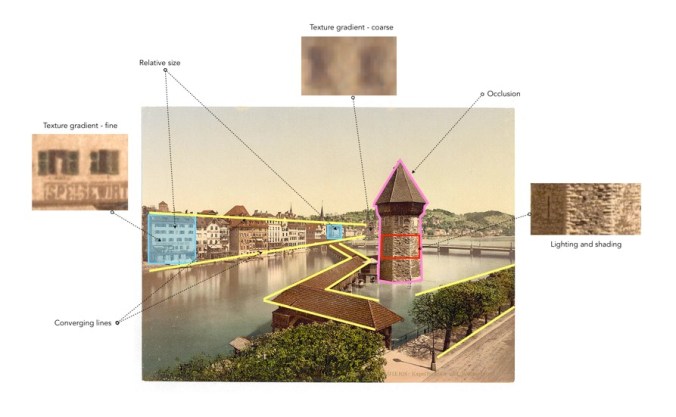

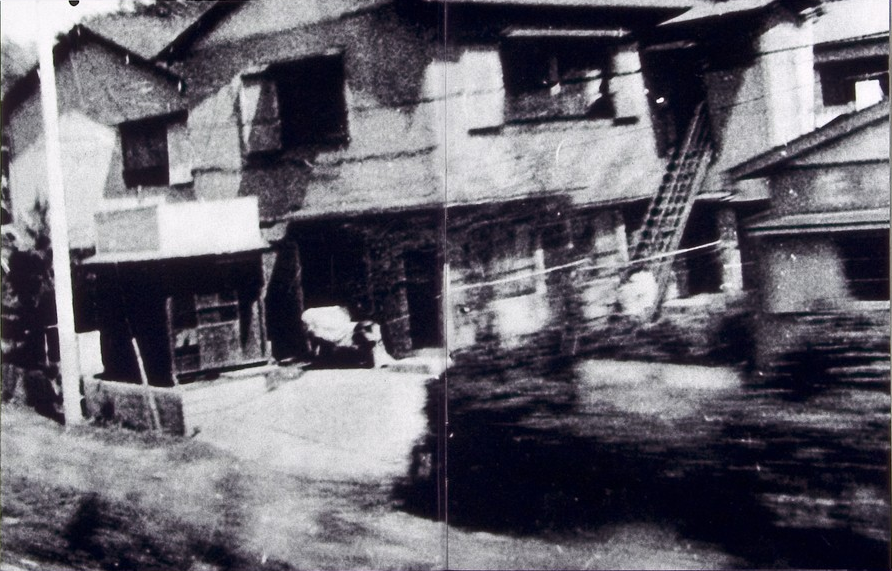

The aim of Provoke was to rethink the relationship between word and image, in essence to create a new language. It was to challenge the traditional view of the beauty of photographs, and their function as narrative, pictorial entities. The photographs were fragmented images that rethought the established aesthetic of photography. The photographs they published were an collection of “coarse, blurred and out-of-focus” images, characterized by the phrase Are‑Bure‑Boke (pronounced ah-reh bu-reh bo-keh). It roughly translates to “rough, blurred and out-of-focus”, i.e. grainy (Are), blurry (Bure) and out-of-focus (Boke).

They tried random triggering, they shot into the light, they prized miss-shots and even no-finder shots (in which no reference is made to the viewfinder). This represented not just a new attitude towards the medium, but a fundamental new outlook toward reality itself. Of course that is not to say that every photograph had the same characteristics, because there are many different ways of taking a picture. The unifying characteristic is the ability to push beyond the static boundaries of traditional photographic aesthetics. Provoke provided an alternative understanding of the post-war years, one that had traditionally been quite Western centric.

Further reading:

- As the three volumes of Provoke became very rare (and expensive), they were recently reprinted and can be found on the Shashasha website.

- Photopedagogy lesson on Provoke.

- aperture – The Provoke Movement, by Tsuyoshi Ito