When you look at modern lenses, there isn’t much that sets them apart. They are usually pretty plain black cylinders, partially due to the consistency of modern lens design. The same could not be said of vintage lenses. Maybe this has something to do with the fact that many vintage lenses were made by companies that focused purely on lenses, and as such tried hard to differentiate their lenses from their competitors. For example a company like Meyer Optik Gorlitz manufactured lenses for cameras using the Exakta mount had to compete for the consumer spending with lenses from a myriad of other companies (at least 25-30).

Over time the appearance of lenses naturally changed, as new materials were introduced, often for the purpose of reducing the overall cost of lenses. For example, many early 35mm lenses had a shiny, chrome-like appearance. The earliest, pre-war lenses were often made of chrome-plated brass. As the Second World War progressed, shortages or re-direction of materials like brass led some manufacturers had begun to transition towards aluminum, which was both less expensive, easier to manufacture, and produced a lighter lens. While these early aluminum lenses were aesthetically pleasing there was little that differentiated them in a world where there was an increasing number of 3rd party lens manufacturers.

When it first appeared as a lens material, aluminum was chic. The 1950s was the age of aluminum, which was a symbol of modernism. Many of the largest aluminum producers pursued new markets to absorb their increased wartime production capacity, used in everything from drink cans to kitchenware and Airstream trailers (there was also extra aluminum from scrapping of war surplus aircraft etc.). These aluminum lenses were initially clear-coated to reduce the likelihood of tarnishing, but eventually anodized to provide a robust black coating. Also in the 1950s, lens manufacturers to realize changing trends in lens design – buyers had moved away from the idea of pure practicality, and focused also on design. This wasn’t really surprising considering the broad scope of modernist design during this period – design tended to favour sleek and streamlined silhouettes. It is interesting to note that most of the aesthetically pleasing lenses of the post-1950 period originated from Germany.

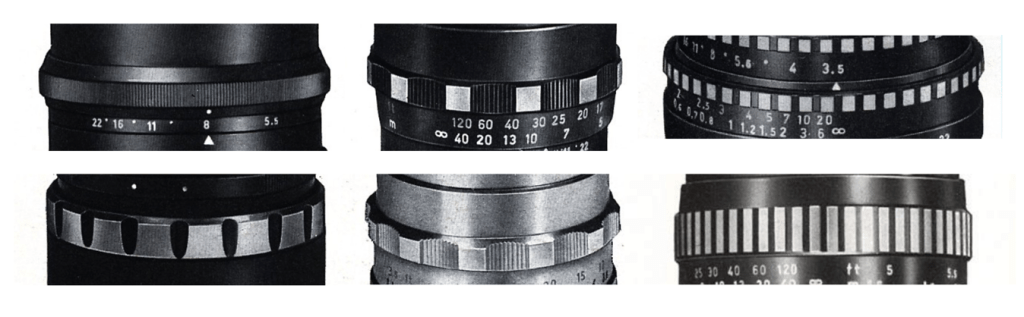

The first notable change was the gradual move towards what in German manufacturers called the “berg und tal” design, or rather “mountain and valley” design of the grips on a lens – usually knurled depressions milled into the surface of the ring (but also the opposite like the lenses of Steinheil where the depressions are smooth and the mountains are knurled). English-speaking regions often referred to this as a “knurled grip”. Appearing in the early 1950s, it was particularly common for focusing rings, making them more prominent, and likely more ergonomic, i.e. easier to grip. Some lenses started with the focusing ring, and eventually used the same design on the aperture ring. Prior to this most lenses used a simple straight knurl on the adjustment rings.

Towards the end of the 1950s, the pure-aluminum design transitioned to a combination of silver and black anodized aluminum. The lens bodies themselves were mostly black, with the “berg und tal” designs alternating between black and silver. This alternating pattern is what is colloquially known as “zebra” design. Many lens manufacturers utilized the zebra aesthetic in one form or another including Schacht, Enna, Steinheil, Schneider-Kreuznach, Meyer Optik, Rodenstock, ISCO etc..

Zeiss probably produced the best known examples of the zebra aesthetic design with the Pancolar and Flektogon series of lenses. Although these lenses did not appear until the early 1960s, they bypassed the more prominent berg-und-tal in favour of a much subdued black-and-white knurled grip (which is also something Meyer Optik did with lenses like the Lydith 30mm). This design for both focusing and aperture rings replaced the rough textured rings of the earlier lenses. Some call these lenses the “Star Wars lens”. The Pancolar 50mm f/2 appeared ca. 1960 in the form of an f/2 lens with dual black-silver body encompassing a “converging-distance” depth of field range indicator, and either a textured or nubbed rubber focusing ring. This evolved a few years later to the classic “zebra” design, shortly before the release of the classic Pancolar 50mm f/1.8, which also sported the zebra design. By the 1970s, the Pancolar 50mm f/1.8 had morphed into a complete black configuration with a large rubber cross knurling focus grip and a finely knurled aperture ring.

Japanese manufacturers transitioned from aluminum/chrome to black bypassing the zebra design. The one exception seems to be the Asahi Auto-Takumar 55mm F/1.8, which appeared in 1958, but is the sole example of zebra design (at least by Asahi). Japanese manufacturers did however embrace the berg-and-tal design.

By the mid-1960s many camera manufacturers were producing their own lenses, particularly in Japan. As such lenses became more consistent, with little need to compete with other lens manufacturers. There were still 3rd party lens manufacturers but their perspective was to concentrate more on the manufacture of inexpensive lenses. Most lenses transitioned to using standardized, nonchalant black aluminum lenses, with the onus being more on the quality of the optics. Grips transitioned from berg-und-tal to a flatter, square-grooved style, still using a in black/chrome contrast (which likely resulted in a cost saving). By the mid-1970s focus rings were provided with a ribbed rubber coating, still common today on some lenses.

Today, the sleek aluminum lenses are sought after because of their “retro” appeal, as too are the zebra lenses.