Vintage “normal” lenses most often range from 40mm to 58mm, although the greatest number of theses lenses fall in the range 50-58mm. A lens which satisfies the ideal of being “normal” has a focal length close to the diagonal of the film format. So, 24×36mm = 43mm. 35mm is an exception to this rule – when Oskar Barnack developed the original Leica he fitted it with a 50mm Elmax to ensure the most could be done with the small negative area. From that, the 50mm became the ubiquitous standard. With the proliferation of 35mm single lens reflex (SLR) cameras, manufacturers in the early years tended to fit 55-58mm lenses. But why was this the norm instead of 50mm?

There are a variety of reasons. Let’s start at the beginning.

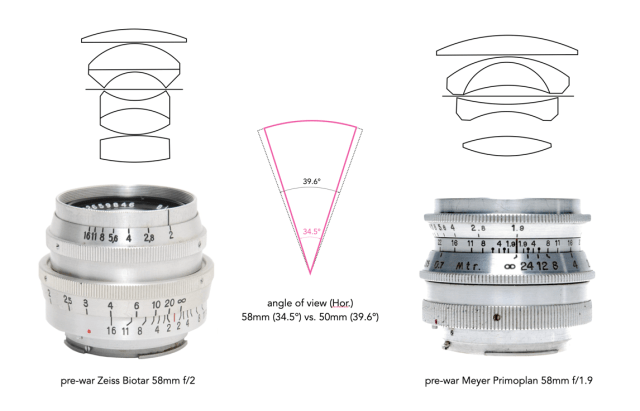

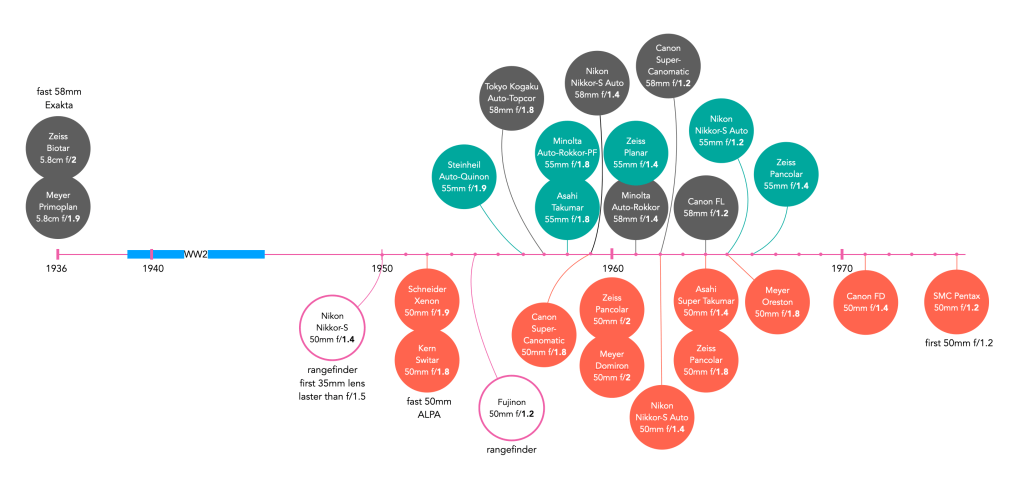

When Ihagee (Dresden) released the worlds first 35mm SLR in 1936 it had a series of standard lenses, but basically there were two categories: the slow 5.0cm lenses which ranged from f/2.8 to f/3.5 (e.g. Tessar, Xenar), and the marginally faster, 5.0cm/5.8cm f/1.9-2.0 lenses, e.g. the 5.8cm f/2 Biotar (developed for the Exakta). The first post-war Exakta did not appear until 1949, the Exakta II, along with a cornucopia of standard lenses from numerous manufacturers, but the fastest 50mm lens was still the Zeiss Tessar f/2.8.

The “… to 60-mm…” was included in the normal-lens category only because such lenses are frequently supplied as standard optics on single-lens reflexes. The reason is that in many cases the designers have found it easier to meet the special requirements of through-the-lens focusing by going to a slightly longer focal lens. Fifty-eight mm is the most common choice.

Bob Schwalberg, “Interchangeable lenses by the carload”, Popular Photography, pp.36-38,197 (May, 1956)

The 35mm SLR experienced a rapid increase in popularity among amateur photographers in the 1950s, especially after manufacturers realized that the installation of a prism viewfinder made handling this type of camera much easier. With this came the need for faster lenses, for two reasons – the ability to take pictures in poor lighting conditions, and a brighter viewfinder image makes it easier to focus. Lens such as the Biotar 58mm f/2 were considered to have a long focal length – to the amateur this was less than favourable, because they would get less coverage than 50mm. Over the course of the 1950s, manufacturers worked on new lens configurations to increase the speed of 50mm lenses, however 55mm and 58mm lenses still maintained the edge in terms of speed.

The original Asahi Takumar lenses which evolved with the 1952 Asahiflex (M37 mount), only included a single 50mm lens, with a speed of f/3.5. Both the 55mm (f/2.2) and 58mm (f/2.2,2.4) lenses had faster speeds. The 58mm f/2.4 in 1954, which became the standard lens for the Asahiflex II. The Auto Takumar’s focused on 55mm lenses with both f/1.8 and f/2.0 lenses. It was not until the Super-Takumar’s appeared in 1964, that the fast 50mm became more normal, with the f/1.4 lens. Canon didn’t produce much in the way of fast SLR lenses until the FL series lenses, introduced for the Canon FX, and FP, which debuted in 1964. Here there was a fast 50mm f/1.4, yet the f/1.2 lenses were still in 55mm and 58mm. In truth, even 50mm lenses faster then f/1.8 did not appear in Japan until the mid-1960s. many of the super-fast 50mm lenses were developed for rangefinder cameras, and never extended to SLRs.

The post-war German 50mm lenses did not really get much faster than f/1.8. This is in part because although the competition in Japan spurned a lens “speed-war”, the same was not true in Germany. The fastest lenses of the early 1950s was still the Biotar 58mm f/2, and Meyer Primoplan 58mm f/1.9. By 1960, at least for the Exakta Varex there was now a 50mm f/2 in the guise of the Zeiss Pancolar. By 1962 Exakta brochures had sidelined the Biotar 58mm, in favour of the Meyer Optik Domiron 50mm f/2. The Japanese had however established f/1.8 as the standard speed for a 50mm. The Zeiss Pancolar 50mm f/1.8 is an extremely good lens, but did not appear until 1964. Similarly the Görlitz Oreston 50mm f/1.8 did not appear until 1965. One of the reasons these “average” speed lens were produced is volume. The production of Praktica cameras in the mid-1960s reached 100,000 units per year, all of which needed a standard lens. It was all about economics.

It was not the same in the world of 35mm rangefinder cameras. There was already a fast pre-war lens, the Zeiss Sonnar 50mm f/1.5 (7 elements/3 groups). The original Sonnar was designed with six elements in three groups, which would allow a maximum of an f/2 aperture. In 1931, a redesign with a new formula was developed with seven elements in three groups, allowing a maximum aperture of f/1.5. But the problem with the Sonnar design was that for shorter focal lengths, e.g. 50mm, it had a short back-focal-distance (BFD) which although being an advantage in rangefinder cameras, made them incompatible with most SLR cameras due to the space taken up the (retracting) mirror (which increases the flange focal distance). The set-up is illustrated in Figures 3 and 4. In Figure 3, the lens is shown how it would normally appear in a Contax rangefinder camera. However if the same lens were used in a 35mm Exakta (Figure 4), there would be an issue because the BFD would be too short because of the increase length of the flange focal distance, which is due to the clearance needed by the mirror.

This illustrates the biggest problem with making a fast 50mm lens was the fact that the addition of a mirror in the SLR meant that lenses had to be further from the film plane, requiring a redesign of the optical formula of the lenses. The easier solution was to marginally increase the focal length.

Trying to adapt the Sonnar design to 50mm was probably cost prohibitive as well. The Sonnar’s had large glass elements with massive core thickness, which required very thick sheets of raw glass, and they had strongly spherical lens surfaces. The latter issue lead to more issues when cementing lenses together, i.e. it was time consuming and required great precision. The Tessar 50mm’s on the other hand could be produced much more efficiently which made them less expensive to produce. The only real Sonnar design for SLRs was produced by Asahi, the Takumar 58mm f/2 from 1956 (6 elements/4 groups).

Partly to more easily provide clearance, for the moving mirror, and partly to produce a larger viewing image, the post-pentaprism wave of SLRs got off to a slow start in the early fifties with 58-mm standard lenses. Since physiological factors dictate an eyepiece of approximately 58mm focus, the choice of this focal length for the normal lens gave a 1-1, fully life-sized viewing image.

Bob Schwalberg, “The shifty fifty”, Popular Photography, pp.73-75,118,119 (Sep., 1970)

Some of the reasons were likely simpler than all that. When Carl Zeiss released the Contax S, the world’s first 35mm production SLR camera with an eye-level prism viewfinder and exchangeable lenses in 1949, the camera came with the Biotar 58mm f/2 as the kit lens. The popularity of the Biotar, spurned others to adopt a similar lens design. One of the reasons the Biotar had a large following was because it was felt that it provided a deeper and more three-dimensional image. There were many Biotar types of lenses, but at 58 mm the image in the prism finder had approximately the same scale as one viewed with a naked eye. Last but not least, as we have seen in a previous post, 58mm approximates the 30° central symbol recognition of the HVS, which means it quite nicely fits into the scope of focused human vision.

Aside from mechanical issues, there may have been other more aesthetic reasons for the 55mm/58mm lens frenzy. There is an experiential rule that says a portrait lens for half-body portrait should be about 1.5 times the focal length of a “normal” lens (2 times for head-shots). If we take the normal range to be about 40-55mm, this would make an appropriate lens about 60-82.5mm. So a 58mm lens is quite close to the minimum for half-body portraits. No surprise that the upper bound is also close to 85mm, a favourite with portrait photographers. Why did this matter? Because of the large market for amateur photographers in the 1950s who were interested in taking pictures of family etc.

The trend of 55/58mm lenses had reversed itself by the mid-1960s, with 50mm lenses becoming faster likely due to the advent of faster glass, and better optical formulae.