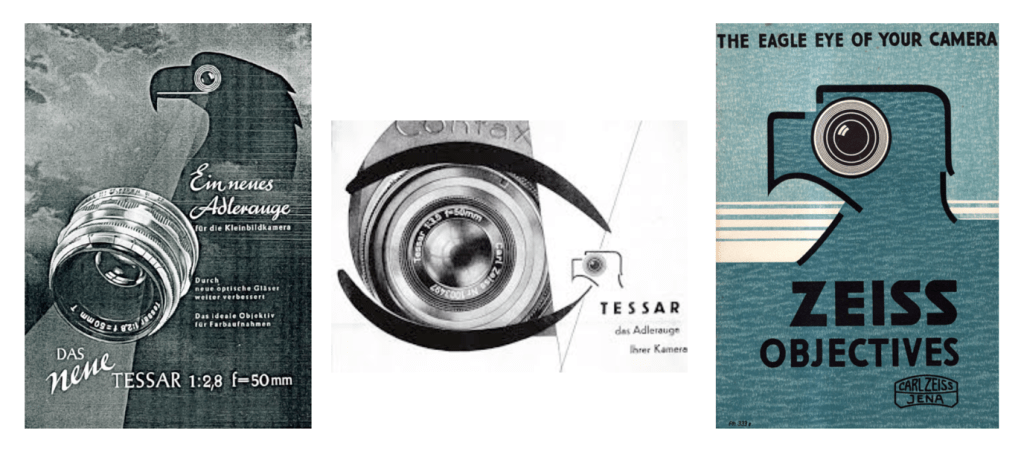

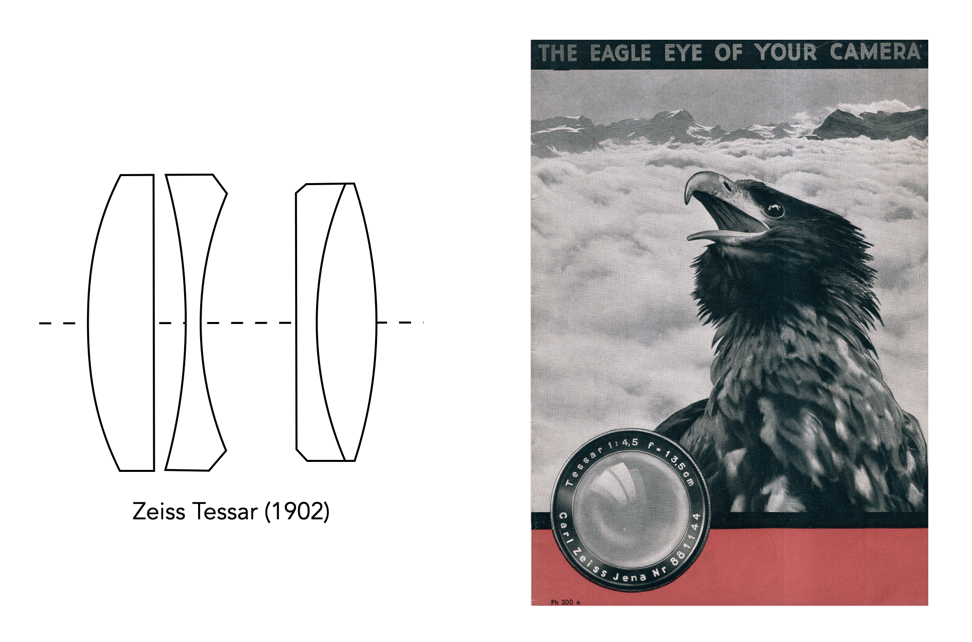

It was Zeiss who came up with the “the eagle eye of your camera” slogan in the 1930s to advertise their lenses (or in German “Das Adlerauge Ihrer Kamera” – eagle eye being Adlerauge) [1]. Of course they were mostly talking about the Tessar series of lenses.

“The objective should be as the eagle’s eye, whose acuity is proverbial. Where its glance falls, every finest detail is laid bare. Just as the wonderful acuity of the eagle’s eye has its origin, partly in the sharpness of the image produced by its cornea and lens, and partly in the ability of the retina – far exceeding that of man’s vision – to resolve and comprehend the finest details of this delicate image, so, for efficiency, must the camera be provided on the one hand with a ‘retina’ (the plate or film) of the highest resolving power – a fine grain emulsion – and on the other hand with an objective which can produce the needle sharp picture of the eagle’s lens and cornea.”

The Eagle Eye of your Camera (1932)

Zeiss took great lengths to use this simile to describe their lenses. A lens must have the sharpness of an eagle’s eye, and the ability to admit a large amount of light – sharpness and rapidity over a wide field of view – the Zeiss Tessar. While Leica named their lenses to indicate their widest aperture, Zeiss instead opted to name their lenses for the design used. Indeed the Tessar came in numerous focal length/aperture combinations, from a 3¾cm f/2.8 to a 60cm f/6.3.

The Tessar is an unsymmetrical system of lenses : 7 different curvatures, 4 types of glass, 4 lens thicknesses, 2 air separations, i.e. 17 elements which can be varied. Zeiss went to great lengths to disseminate the message about Tessar lenses:

- sharp, flare-free definition

- great rapidity (allowing short instantaneous exposures)

- exceptional freedom from distortion (obviating any objectionable curvature)

- good colour correction

- compact design (so that light falling off near the edge is reduced to a minimum)

- sufficient separation of the components of the lens (to allow a between lens shutter)

- the use of types of glass as free as possible of colour

- reduction to the minimum of the number of lenses, and particularly of glass-air surfaces

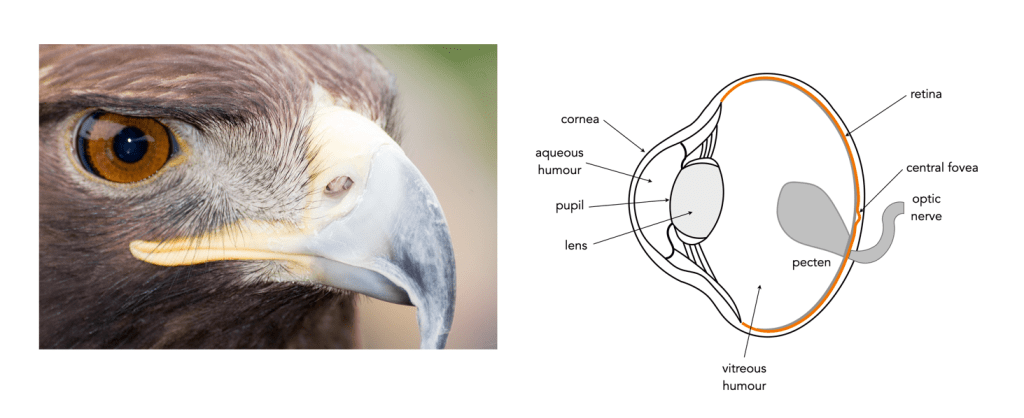

It is then not surprising that Zeiss choose to compare the lens to an eagle’s eye. The eagle is considered to be the pinnacle of visual evolution. They can see prey from a distance – it is said they can see a rabbit in a field while soaring at 10,000 feet (1.9 miles or 3km). It was Aristotle (in 350BCE) who in his manuscript “Aristotle, History of Animals” pointed out that “the eagle is very sharp-sighted”. The problem however is that it’s not really possible to compare a simple lens against the eye of a living organism. Zeiss was really comparing the lens of an eagle’s eye against the Tessar, or rather the Tessar and the human eye behind it, because the camera lens is just a part of the equation of analog picture taking. So how does an eagle eye compare to a human one?

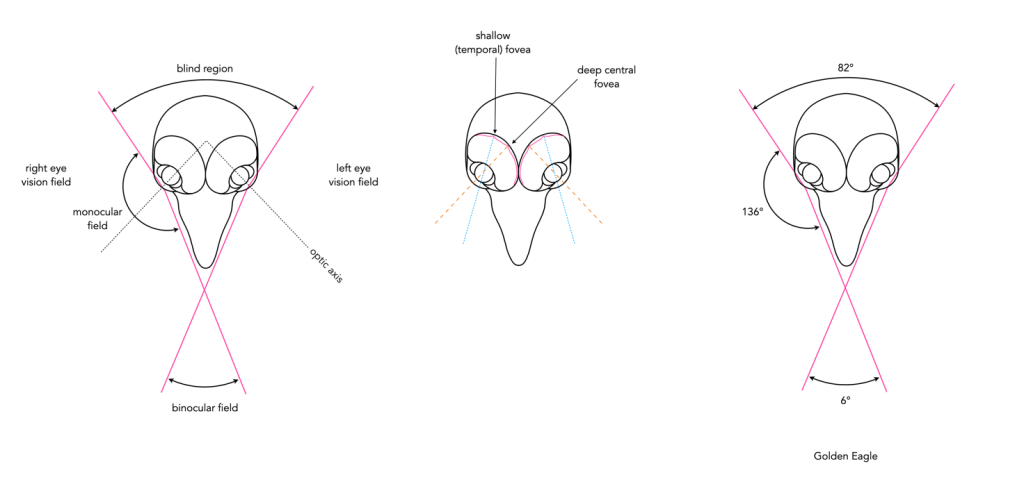

It’s kind of hard to really compare eyes from different species because they are all designed to do different things. In all likelihood, human eyes have evolved over time as our environment changed. In birds, unlike humans, each eye looks outwards at a differing scene, and the overlap of the visual field of both eyes, i.e. the binocular region, is relatively small. This is typically less than 60° in birds, versus 120° in humans, and can be as narrow as 5-10° in some species. Because of this a birds total visual field is quite extensive, with just a narrow blind region behind the head. Eagle’s have a highly developed sense of sight which allows them to easily spot prey. They have 20/5 vision compared to the average human who has 20/20 vision. This means they can see things at 20’ away that humans only have the ability to see at 5’. They have fixed eye sockets, angled 30° from the mid-line of their face, giving them a 340° view. Many also have violet-sensitive visual systems, i.e. the ability to see ultraviolet light and detect more colours than human eyes can.

The first thing to consider may be the size of the eye. We will pick one eagle to compare against human vision, and the best option is the (European) Golden Eagle, because it is quite common in Germany. The average weight of a Golden Eagle is 6.1kg, versus the average weight of a European (human) at 70.8kg. If we work on the principle that an eagle’s eye is similar in weight to a human eye (ca. 7.5g) then an eagle’s eye would comprise 0.12% of its body weight, versus 0.01% of a human. So for the human’s eye to be equivalent in mass based on eye:body weight ration, it would need to be 85g. But this is really an anecdotal comparison, the bigger picture lies with the construction of the eye.

One of the reasons birds of prey have such incredible eye-sight is the fact that their deeper fovea allows them to accommodate a greater number of photoreceptors and cones. The central fovea in an eagle’s eye has 1 million cones per square millimetre, compared to 200,000 in a human eye. One way that eagles do this is by having increased resolution. This is achieved by have reduced space between their photoreceptors. Due to the physics of light, the absolute minimum separation between cones for an eye to function correctly is 2µm (0.002mm). As the space between the photoreceptors decreases, so too does the minimum size of the detail.

The other thing of relevance is that while humans have one fovea, eagles generally have two – a central fovea used for hunting (cone separation 2µm, versus human cone separation of 3µm), and a secondary fovea which provides a high resolution field of view to the side of their head. So like a camera sensor, more cones means better resolution. In context Robert Shlaer [2] suggested that the resolution of a Golden eagle’s eye may be anywhere from 2.4 to 2.9 times that of a human, with the Martial Eagle somewhere between 3.0 and 3.6 times. The spatial resolution of a Wedge-Tailed eagle is between 138-142 cycles per degree [3], while that of a human is a mere 60. Their foveae are also distinctly shaped, deep and convex, as opposed to the rounded and shallow single fovea of human eyes. In a 1978 article for the scientific journal Nature, Snyder and Miller [4] proposed that the unique shape of foveae found in some birds of prey may act like a telephoto lens, magnifying their vision, which is perhaps why these feathered predators can spot food from so far in the sky. Like humans, eagles can change the shape of their lens, however in addition they can also change the shape of their corneas. This allows them more precise focusing and accommodation than humans.

But Zeiss themselves harked on the limitations of the simile: The fact that an eagle can quickly turn its head to allow for viewing in any direction; the fact that the retina is curved, not flat. From the perspective of resolution the ads were true to form, however the other aspects of the an eagle’s vision did not ring true. Yes, telephoto lenses based on the Tessar design could certainly see further than a human, and given the right lens and film could see into the violet spectrum, but Zeiss’s claim was really more about finding a way to describe it’s lenses in a provoking manner, one which would ultimately sell lenses.

Further reading:

- Zeiss Brochure: “The Eagle Eye of your Camera”, Carl Zeiss, Jena (1932)

- Robert Shlaer, “An Eagle’s Eye: Quality of the Retinal Image”, Science, 176, pp. 920-922 (1972)

- Reymond, L. (1985). Spatial visual acuity of the eagle Aquila audax: A behavioural, optical and anatomical investigation. Vision Research, 25(10), 1477–1491.

- Snyder, A.W., Miller, W.H., “Telephoto lens system of falconiform eyes”, Nature, 275, pp.127-129 (1978)