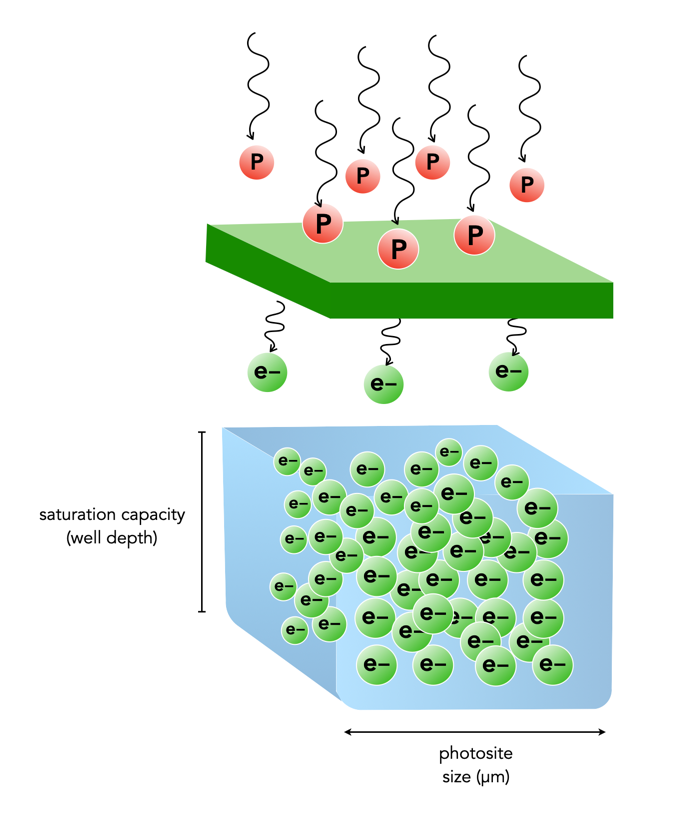

When photons (light) enter a lens of a camera, some of them will pass through all the way to the sensor, and some of those photons will pass through various layers (e.g. filters) and end up in being gathered in the photosite. Each photosite on a sensor has a capacity associated with it. This is normally known as the photosite well capacity (sometimes called the well depth, or saturation capacity). It is a measure of the amount of light that can be recorded before the photosite becomes saturated (no long able to collect any more photons).

When photons hit the photo-receptive photosite, they are converted to electrons. The more photons that hit a photosite, the more the photosite cavity begins to fill up. After the exposure has ended, the amount of electrons in each photosite is read, and the photosite is cleared to prepare for the next frame. The number of electrons counted determines the intensity value of that pixel in the resulting image. The gathered electrons create a voltage which is an analog signal -the more photons that strike a photosite, the higher the voltage.

More light means a greater response from the photosite. At some point the photosite will not be able to register any more light because it is at capacity. Once a photosite is full, it cannot hold any more electrons, and any further incoming photons are discarded, and lost. This means the photosite has become saturated.

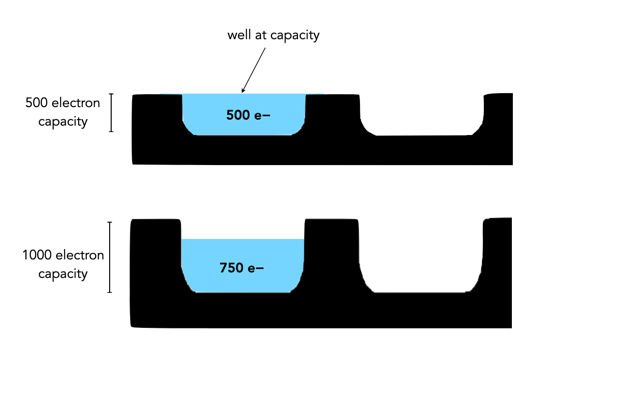

Different sensors can have photosites with different well-depths, which affects how many electrons the photosite can hold. For example consider two photosites from different sensors. One has a well-depth of 1000 electrons, and the other 500 electrons. If everything remains constant from the perspective of camera settings, noise etc., then over an exposure time the photosite with the smaller well-depth will fill to capacity sooner. If over the course of an exposure 750 photons are converted to electrons in each of the photosites, then the photosite with a well-depth of 1000 will be 75% capacity, and the photosite with a well-depth of 500 will become saturated, discarding 250 of the photons (see Figure 2).

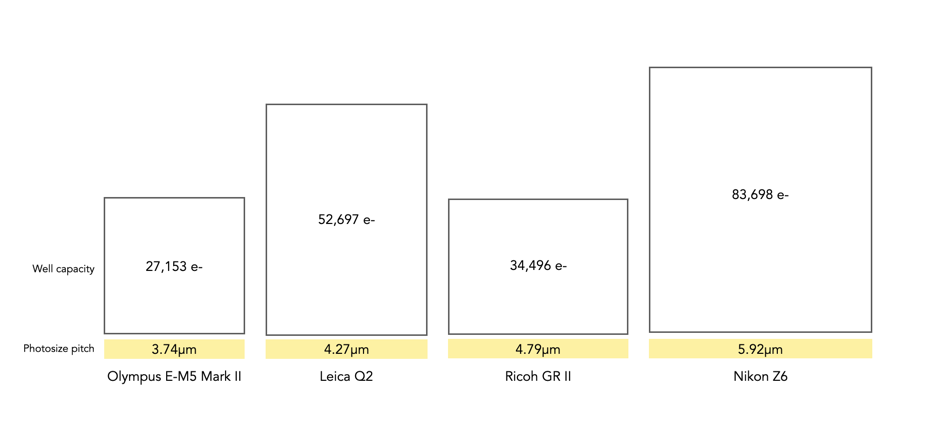

Two photosite cavities with the same well-capacities, but differing size (in μm) will also affect how quickly the cavity fills up with electrons. The larger sized photosite will fill up quicker. Figure 3 shows four differing sensors, each with a different photosite pitch, and well capacity (the area of each box abstractly represents the well capacity of the photosite in relation to the photosite pitch).

Of course the reality is that electrons do not need a physical “bin” to be stored in, the photosites are just shown in this manner to illustrate a concept. In fact the concept of well-depth is somewhat ill-termed, as it does not take into account the surface area of the photosite.